Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Noor trembles in the cold afternoon light in the courtyard, not from cold, but from fear.

Dressed in her thick winter coat, she has come to complain to the men of Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), the new de facto rulers of Syria, and the new law in the city.

She begins to cry as she explains that three days earlier, shortly before nine at night, armed men had arrived in a black van at her apartment in an exclusive neighborhood of the city of Latakia. Together with her children and her husband, an army officer, she was forced to go out in her pajamas. The leader of the gunmen then installed his own family in his house.

Darren Conway/BBC

Darren Conway/BBCNoor – not her real name – is Alawite, the minority sect from which the Assad family comes and to which many members of the political and military elite of the old regime belonged. The Alawites, whose sect is a branch of Shiite Islam, make up about 10% of Syria’s population, which is majority Sunni. Latakia, on the Mediterranean coast of northwestern Syria, is its heart.

As in other cities, a number of different rebel groups have rushed to fill the power vacuum left after Assad’s soldiers abandoned their posts. The regime had exploited sectarian divisions to maintain its grip on power, now Sunni Islamist HTS has pledged to respect all religions in Syria. But the Alawite population of Latakia is afraid.

Some people have not even left their homes since the regime change because they fear that there will be a reckoning and that they will have to pay a high price for supporting the old regime.

Noor shows CCTV footage of her apartment to Abu Ayoub, 34, HTS general security commander. In the film, a group of bearded fighters, some in baseball caps and others in military uniforms, appear at the door of his house.

Quentin Sommerville/BBC

Quentin Sommerville/BBCThey are not from HTS, he says, but from another group, rebels from the northern city of Aleppo.

“They broke down the door. There were 10 militants at our door and another 16 waiting on the street with three cars,” Noor tells Abu Ayoub. His men are mostly from Idlib and Aleppo, where the HTS and allied rebel factions were based before launching the offensive that toppled Assad three weeks ago. They stand dressed in combat fatigues, holding their rifles and listening intently as she describes how the family’s belongings were thrown into the street.

HTS was once aligned with Al Qaeda and is still banned as a terrorist organization by most Western countries, although the United Kingdom and the United States say they have been in contact with the group. In a matter of weeks, he has gone from being an enemy of the state to being the law of the land. Abu Ayoub and his men are adapting to the change in roles from revolutionaries to police officers.

Noor is just one of a long list of whistleblowers who have gone to his general security post with complaints. The base, the city’s former military intelligence headquarters, was perhaps the most feared place in Latakia. Now it’s chaos, with broken radios and equipment scattered around the yard. Broken portraits of Bashar al-Assad lie on the ground.

A man joins the queue of those who file complaints. He has a black eye, broken ribs, and his shirt is torn and bloody. He says men from Idlib broke into his apartment.

Darren Conway/BBC

Darren Conway/BBC“Some of them were civilians, others were dressed in military clothing and were masked,” he says. “They beat my daughter and pointed guns at my son’s head. They stole money, they stole gold.”

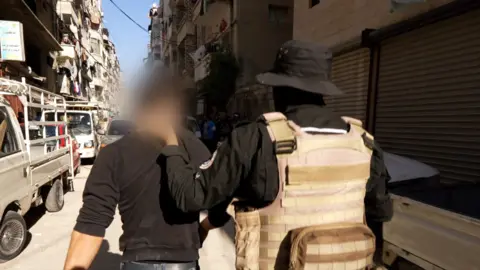

Every call here is a show of force, especially with so many armed groups in the city. With the man’s son leading them, HTS security forces head into one of the poorest neighborhoods, traversing a maze of side streets, past junkyards and garbage dumps.

Armed police take up positions along the street and at the apartment door. Two suspects are taken to the police station for questioning.

But they barely have time to draw their weapons when there is another complaint, a dispute over gas cylinders that left another man beaten.

He says three men pointed guns at him.

Darren Conway/BBC

Darren Conway/BBCAnother car race towards a busy commercial and residential neighborhood. When the police take a suspect out onto the street, his face still bloody from the earlier fight, local women come out to their balconies and shout “Shabiha! Shabiha!” They are accusing the suspect of being a member of the shadowy militia, made up mostly of Alawite men, who did the Assad regime’s dirty work.

Since its rapid advance to victory throughout Syria, the Islamist HTS has been committed to maintaining peace and protecting all minorities in the country. And every day Abu Ayoub has to fulfill that promise.

“Some infiltrators in the revolution, some saboteurs and some weak-minded people take advantage of the situation in the recently liberated areas,” he says.

Abu Ayoub admits that the situation in the city was “a little chaotic”, but turns his attention to Noor. “We are here now, we were not here when the army left. At first we were in Damascus and then we arrived. They are thugs and we will evict them from their house. We will return their belongings. You have my word,” he said. And with that he orders his men to get into their trucks and with the sirens blaring they head to the apartment.

Latakia is a liberated city. Last Friday, tens of thousands of people from all sects gathered in the streets to celebrate the fall of the Assad dynasty. In a city square, they sat on the pedestal where the statue of Hafez al-Assad, Bashar’s father, who ruled for 29 years before his death in 2000, once stood, and joyfully waved the flag of a Syrian free.

The message that day was unity, a single Syria, without sectarian divisions. But after half a century of tyrannical rule by a regime that stoked sectarian hatred and warned that Alawites would be massacred if they ever lost power, it is an adjustment, to say the least.

On Saturday, three HTS fighters were killed and 14 wounded on the outskirts of the city in what was said to be a shootout with a criminal gang. HTS, which is trying to remain calm, claims that there was no sectarian element in the attack.

On the way to Noor’s apartment, the HTS convoy speeds through the streets and passersby cheer and flash the peace sign.

Quentin Sommerville/BBC

Quentin Sommerville/BBCThe new Syrian flag, with its green stripe instead of red and three red stars instead of two green ones, is common on shop shutters and balconies. But in Alawite areas, most people watch in silence as the convoy moves forward. There are fewer new flags in evidence.

Azam al-Ali, 28, a security officer at HTS in Deir al-Sour, eastern Syria, is sitting in the front seat. After so much oppression, he says, it will take time for people to trust authority again.

“The majority of the oppressed who come with complaints belong to two sects, the Sunnis and the Alawites. We don’t differentiate. But the extreme poverty left by this regime caused this enormous chaos,” he tells me as the traffic separates from the convoy. .

And he notes that the Alawites, some of whom were among the poorest in Syria, also suffered under the Assad regime.

We arrive at Noor’s apartment and half a dozen armed HTS men run up the stairs.

Darren Conway/BBC

Darren Conway/BBCThe woman behind the door refuses to open, but after some negotiations the door opens and she and her family are ordered to leave. Noor goes in to look for clothes and books for her daughter who is studying for her exams. Weapons and ammunition belonging to the rebels are confiscated.

“When I went to HTS today I was terrified,” says Noor. “Their appearance was so intimidating and scary. Honestly, they were so nice.”

But she won’t return to the apartment. One nightmare has ended in Syria and another has begun for the Alawites, he says.

As she grabs her belongings, Noor says she no longer feels safe in her house.

“It is impossible for me to live here again. I have hope, but not in the near future. At the moment I don’t dare.”