Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

bbc

bbcMyanmar’s once formidable military is cracking from within, riddled with spies secretly working for pro-democracy rebels, the BBC has found.

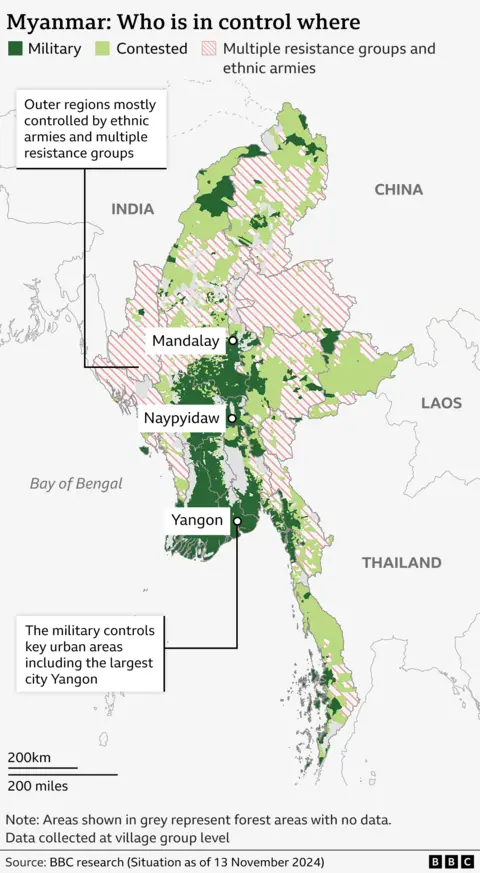

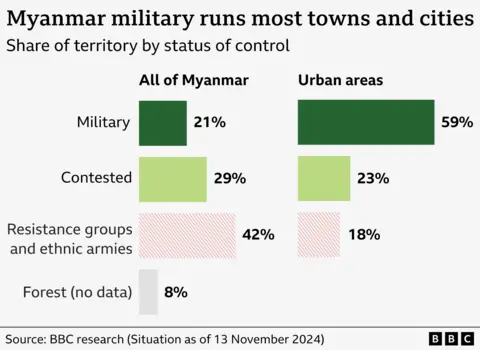

The military only has full control of less than a quarter of Myanmar’s territory, a BBC World Service investigation reveals.

The junta still controls major cities and remains “extremely dangerous”, according to the UN special rapporteur on Myanmar. But it has lost a significant amount of territory in the last 12 months (see map below).

The spy soldiers are known as “Watermelons”: green on the outside, rebellious red on the inside. Apparently loyal to the army but secretly working for pro-democracy rebels whose symbolic color is red.

A major based in central Myanmar says it was the army’s brutality that prompted him to switch sides.

“I saw the bodies of civilians being tortured. I shed tears,” says Kyaw (not his real name). “How can they be so cruel against our own people? We are meant to protect civilians, but now we are killing people. It is no longer an army, it is a force that terrorizes.”

According to the UN, more than 20,000 people have been detained and thousands killed since the military seized power in a coup in February 2021, triggering an uprising.

Kyaw initially considered deserting the army, but decided with his wife that becoming a spy was “the best way to serve the revolution.”

When it is deemed safe to do so, it leaks internal military information to the People’s Defense Forces (PDF), a network of civilian militia groups. Rebels use intelligence to prepare ambushes for the military or to prevent attacks. Kyaw also sends them part of his salary so they can buy weapons.

Spies like him are helping the resistance achieve what was previously unthinkable.

The BBC assessed the balance of power in more than 14,000 village groups in mid-November this year and found that the army only has full control of 21% of Myanmar’s territory, almost four years after the start of the conflict.

The investigation reveals that ethnic armies and a patchwork of resistance groups now control 42% of the country’s land area. Much of the remaining area is disputed.

That BC/BBC

That BC/BBCWatermelon intelligence leaked from within the military is helping to tip the balance. Two years ago, the resistance created a specialized unit to manage the growing network of spies and recruit more.

Agents like Win Aung (not his real name) collect Watermelon leaks, verify them whenever possible, and then pass them on to rebel leaders in the relevant area.

He is a former intelligence officer who defected and joined the resistance after the coup. He says they now receive new watermelons every week and that social media is a key recruiting tool.

His spies, he says, range from low-ranking soldiers to high-ranking officers. They also claim to have Sandías in the military government, “from the ministries to the village chiefs.”

They undergo a strict vetting process to ensure they are not double agents.

Motivations for becoming a spy vary. While in Kyaw’s case it was anger, for a man we call “Moe”, a marine corporal, it was simply the desire to survive for his young family.

His wife, who was pregnant at the time, pressured him to do so, convinced that the military was losing and that he would die in battle.

He began leaking information to the Watermelon unit about weapons and troop movements.

This kind of intelligence is crucial, says pro-democracy rebel leader Daeva.

The ultimate goal of his resistance unit is to take control of Yangon, Myanmar’s largest city and his former home. But they are very far away.

The military retains most major urban areas, home to crucial infrastructure and revenue.

“Attacking and occupying (Yangon) is easier said than done,” says Daeva. “The enemy will not surrender easily.”

Unable to physically penetrate the city, Daeva from his jungle base directs targeted attacks by underground cells in Yangon using Watermelon intelligence.

In August, we saw him make one of those calls. They didn’t give us the details but they told us it was to lead an assassination attempt on a colonel.

“We will do it within the enemy’s security parameters,” he told them. “Be careful, the enemy is losing in all directions,” he added, telling them that this meant they were more likely to be on alert for the possibility of infiltrators and spies.

Daeva says that several major attacks by his unit have been the result of warnings.

“We started with nothing and now we see our success,” says Daeva.

That BC/BBC

That BC/BBCBut this comes at a cost. Watermelons have to live in fear from both sides, as Moe, the navy corporal turned spy, discovered.

Deployed from Yangon to Rakhine – a border region where the army is fighting an ethnic group that aligns itself with the resistance – he had to live with the terror that his intelligence could mean that he himself had been attacked.

In March of this year, his anchored ship was hit by a shell and followed by open fire. “There was nowhere to run. We were like rats in a cage.” Seven of his companions died in the rebel attack.

“Our ability to protect (the moles) is very limited,” admits Win Aung. “We cannot publicly announce that they are watermelons. And we cannot prevent our forces from attacking any particular military convoy.”

He says that, however, when this is explained to the Watermelons, they don’t hesitate. Some have even responded: “When that time comes, don’t hesitate, shoot.”

But there are times when spies can no longer bear the danger.

When Moe was ready to be sent to another dangerous front line, he asked the Watermelon unit to smuggle him to an area controlled by the resistance. They do this using an underground network of monasteries and safe houses.

He left in the middle of the night. The next morning, when he did not show up for duty, the soldiers came to the house. They questioned his wife Cho, but she remained tight-lipped.

After several days on the run, Moe arrived at one of the Daeva bases. Daeva thanked him over a video call before asking him what role he wanted to play next. Moe responded that given his young family, he would like to play a role outside of combat and would instead share his knowledge of military training.

A few weeks later he crossed into Thailand. Cho and the children also fled their home and hope to eventually join him and build a new life there.

The military is aggressively trying to recapture lost territory, carrying out a wave of deadly attacks. In the case of Chinese and Russian-made fighter jets, it is in the air where it has an advantage. He knows that the resistance is far from a homogeneous group and seeks to exploit the divisions between them.

“As the junta loses control, their brutality increases. It’s getting worse. The loss of life… the brutality, the torture as they lose ground, literally and figuratively,” says UN Special Rapporteur Tom Andrews .

The army is also conducting raids for watermelons.

“When I heard about the raids, I stopped for a while,” Kyaw says. He says he always acts like a strong supporter of the military to avoid unwanted attention.

But he is afraid and doesn’t know how long he can stay hidden. Defecting is not an option, as he is worried about abandoning his elderly parents, so for now, he will continue to act as a military spy, hoping to see the day when the revolution ends.

When that day comes, watermelons like Kyaw and Moe will not be forgotten, Win Aung promises.

“We will treat them with honor and allow them to choose what they want to do next in their lives.”

The military did not respond to the BBC’s interview request.

About data:

Investigators commissioned by the BBC questioned multiple sources from February 12 to November 13, 2024 for each of the more than 14,000 village groups to assess the level of military control in their area.

The names and boundaries of the village groups were obtained from Myanmar Information Management Unit, or MIMU, which is hosted by the United Nations Development Program (UNDP).

In all cases, the research team spoke to at least one source with no official affiliation with the military or the opposition, such as academics, charity workers, journalists and local residents.

When sources provided conflicting information for a village group, unaffiliated sources were prioritized and cross-checked with media reports.

The responses were divided into three possible control categories:

Some parts of the country are designated as forests and are not assigned to village groups. They have different administrative structures, which mainly deal with resource extraction and conservation. The BBC has chosen to focus on areas of Myanmar that have a clearly defined governance system.

Additional reporting by Becky Dale, Muskeen Liddar, Hla Hla Win, Phil Leake, Callum Thomson, Pilar Tomas, Charlotte Attwood and Kelvin Brown. Methodological support from Professor Lee Jones, Queen Mary University of London.