Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Pokrovsk, in eastern Ukraine, is the birthplace of one of the world’s favorite carols, the Carol of the Bells.

But this year there are few signs of Christmas in the city. Just a layer of snow over deserted streets and skeletal buildings, and the constant sound of intense shelling.

Pokrovsk is Russia’s next target. His troops are now less than three kilometers (two miles) from the city center.

And it’s not just buildings and houses that are being destroyed. Ukraine accuses Russia of also trying to erase its cultural identity, including its associations with that well-known Christmas carol.

Most of the population of Pokrovsk has already fled. The gas supply has been cut off and many houses are left without electricity or water. Those who stay, like Ihor, 59, only come out of hiding to find the essentials. He says it’s like living in a powder keg: you never know when or where the next projectile will land.

Oksana, 43, says she is too afraid to leave her house, but she goes out during a lull in the shelling to look for firewood and coal to keep warm.

He tells me he hopes the Ukrainian military can hold the city, but he thinks that’s unlikely. Pokrovsk, he says, will probably fall.

BBC/Imran Ali

BBC/Imran AliThe city has already prepared for the worst. The statue of its famous composer Mykola Leontovych has already been removed. The music school that bears his name is now closed and empty.

Leontovych may not be well known in the West. But the melody he composed is known throughout the world, with his voice reminiscent of a bell. Leontovych is believed to have written the first scores of the composition, based on a Ukrainian folk song, while living and working in Pokrovsk between 1904 and 1908.

Suspilne Donbas

Suspilne DonbasIn Ukraine it is known as Shchedryk. To most of the world it became known as the Carol of the Bells, after American composer Peter Wilhousky wrote the song’s English lyrics. The use of the tune in the Hollywood film Home Alone helped increase its popularity.

Viktoria Ametova calls it “a masterpiece: the emblematic song of Pokrovsk.” She also taught music until recently in the city, at the school named after Leontovych.

He has now moved to the relative safety of Dnipro. It is where many of Pokrovsk’s former residents still try to keep memories of their former home alive.

Beneath a rescued portrait of Leontovych, Viktoria watches as 13-year-old Anna Hasych plays the familiar chords of the carol on a piano.

BBC/Kostas Kallergis

BBC/Kostas KallergisThe Hasych family fled Pokrovsk this summer. But they are determined not to forget the place they still call home. Anna’s mother, Yulia, says she is glad to see her daughters practicing Shchedryk. “We will not forget the history of our city,” he says.

For Anna, the melody brings back memories. “When I played it at home it seemed happy. It reminded me of winter and Christmas,” he says. “Now it’s more of a sad song for me because it reminds me of home and I really want to go back.”

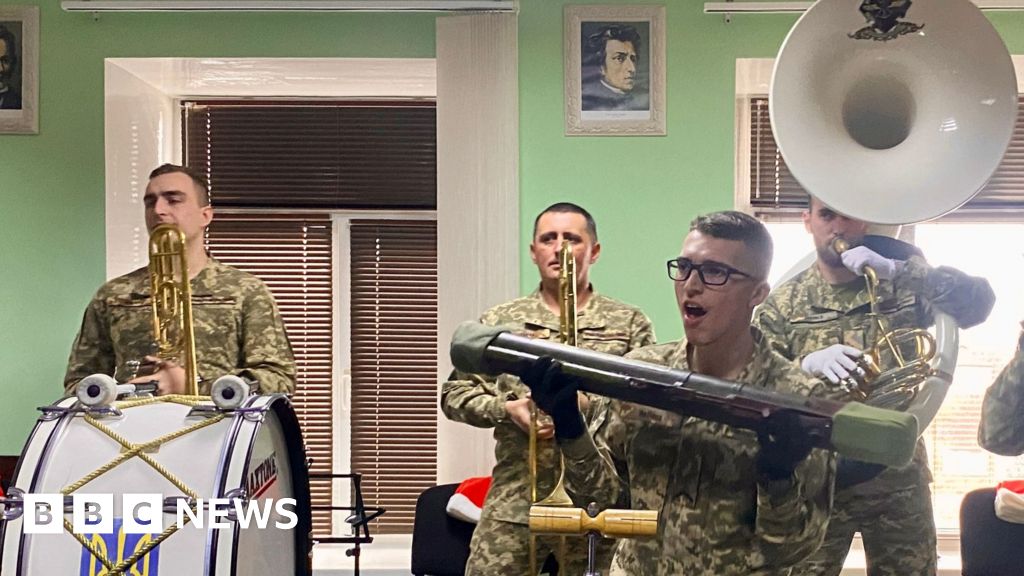

But for a Ukrainian military band, Shchedryk has become a song to inspire resistance. They even practice it in the trenches, using weapons as improvised instruments.

They may be musicians, but their commander reminds me that they are soldiers first and foremost. They have all spent time on the front lines. Colonel Bohdan Zadorozhnyy, the band’s director and director, says the song helps lift the soldiers’ spirits. “Those rhythms energize the guys on the front lines and inspire them to fight,” he says.

Roman, 22, uses the casing of a rocket launcher, filled with rice, to vigorously shake it to the beat of the music. Shchedryk, he says, is “the pride of our country, it is freedom, it is in our souls, I get goosebumps with this song.”

Colonel Zadorozhnyy says Shchedryk shows that Ukraine is a civilized nation, now at war, fighting for its identity.

BBC/Imran Ali

BBC/Imran AliPokrovsk could well fall into Russian hands. But its people are doing everything they can to preserve their culture and identity.

The director of the Pokrovsk History Museum, Angelina Rozhkova, has already rescued and moved to safety most of her prized possessions, including artifacts from Leontovych’s life in Pokrovsk.

Russia, he says, doesn’t just want to take over Ukraine’s territory: “It wants to destroy our culture and everything that is valuable to us.”

Angelina says the people of Pokrovsk understand that they may never return, “but our hearts and souls don’t accept it.” That’s why they are doing everything they can to preserve the past. The new motto is “keeping and saving equals earning.”

It’s hard to say you’re winning when your city is being destroyed. But its people, like Leontovych’s music, are showing extraordinary resilience.

Leontovych’s life came to an abrupt end in 1921 when a Soviet agent shot him. Its composition had become a symbol of the struggle for Ukrainian independence. It still is.

Additional reporting by Hanna Chornous and Anastasiia Levchenko