Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

fake images

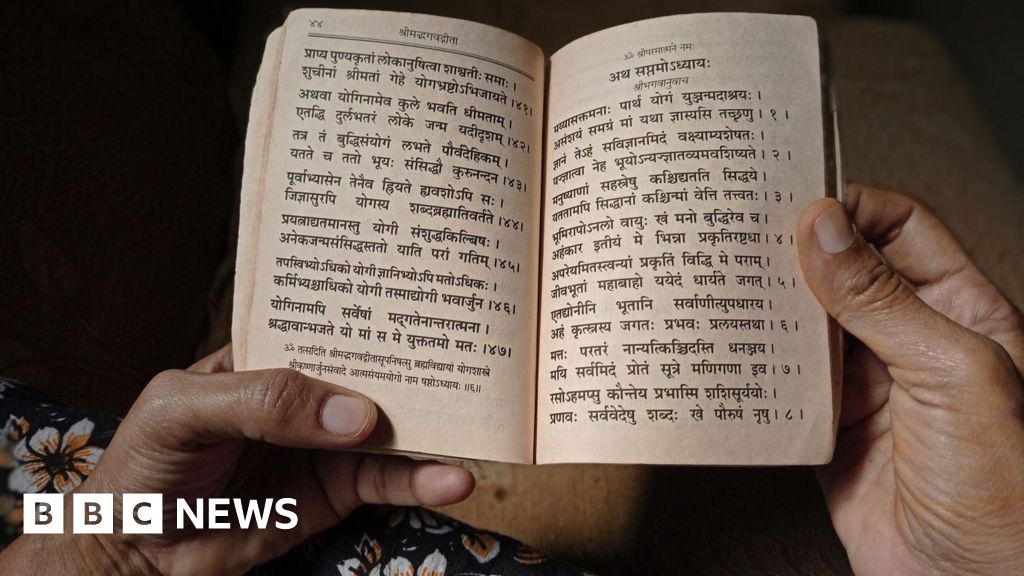

fake imagesIn 1996, Ananya Vajpeyi, a doctoral student in history, discovered the legendary collection of South Asian books at the University of Chicago’s Regenstein Library.

“I have spent time in some of the world’s greatest libraries in South Asia, at Oxford and Cambridge, Harvard and Columbia. But nothing has ever matched the infinite riches that the University of Chicago holds,” said Ms. Vajpeyi, now visiting professor. at Ashoka University in India, he told me.

The 132-year-old University of Chicago houses more than 800,000 volumes related to South Asia, making it one of the world’s leading collections for studies on the region. But how did such a treasure trove of South Asian literature end up there?

The answer is in a program called PL-480a US initiative launched in 1954 under Public Law 480, also known as Food for Peace, a hallmark of Cold War diplomacy.

Signed into law by President Dwight D. Eisenhower, PL-480 allowed countries like India to buy American grains with local currency, easing their foreign exchange burden and reducing American surpluses. India was one of the largest recipients of this food aid, particularly during the 1950s and 1960s when it faced severe food shortages.

Local currency funds were provided at minimal cost to participating U.S. universities. These funds were used to purchase books, periodicals, phonograph records, and local “other media” in several Indian languages, enriching the collections of more than two dozen universities. As a result, institutions such as the University of Chicago became centers of South Asian studies. (The manuscripts were excluded due to Indian antiquity laws.)

fake images

fake images“PL-480 has had astonishing and unexpected consequences for the University of Chicago and more than 30 other American collections,” James Nye, director of the South Asia Digital Library at the University of Chicago, told the BBC.

The process of creating an impressive South Asian library collection was no easy task.

In 1959, a special team consisting of 60 Indians was established in Delhi. Initially focused on collecting government publications, the program was expanded over five years to include books and periodicals. By 1968, 20 American universities were receiving materials from the growing collection, as noted by Maureen LP Patterson, a leading bibliographer of South Asian studies.

in a paper Published in 1969, Patterson recounted that in the early days of PL-480, the team in India faced the challenge of obtaining books from a vast, diverse country with an intricate network of languages.

They needed the expertise of booksellers with a reputation for good judgment and efficiency. Given the size of India and the complexity of its literary landscape, no merchant could handle the acquisition alone, wrote Patterson, who died in 2012.

Instead, distributors were selected from several publishing centers, each of which focused on specific languages or language groups. This collaboration worked perfectly, with distributors submitting titles they were unsure of for approval. The final selection fell on the delhi officePatterson noted.

University of Chicago Photo Archive

University of Chicago Photo ArchiveThe program was keen to acquire a complete collection of Indian fiction in all languages. “Politics spawned a host of detective stories and novels of no lasting value,” Patterson wrote.

In 1963, the choice for purchasing books was reduced to “research-level material” and consumption of fiction in many languages was cut in half. In 1966, more than 750,000 books and periodicals were sent to American universities from India, Nepal, and Pakistan, and India contributed more than 633,000 articles.

“We have sent works like History of India from 1000 to 1770 AD, Crafts in India, Hindu Culture and Personality: A Psychoanalytic Study and more,” said a report at a meeting at a U.S. library about the program in 1967, he said.

Todd Michelson-Ambelang, a South Asian studies librarian at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, wonders whether the region’s vast collections in American and other Western libraries took literary resources away from the Indian subcontinent.

Founded during the tensions of the Cold War and funded by PL-480, its university’s South Asia center grew its library to more than 200,000 titles in the 21st century.

Michelson-Ambelang told the BBC that the removal of books from South Asia through programs like PL-480 “creates knowledge gaps” as researchers there often need to travel to the West to access these resources.

It is not clear whether all the books acquired by American universities in India at that time are still available there. According to Maya Dodd of India’s FLAME University, many books not now available in India can be found in the collections of the University of Chicago library, all marked with the stamp reading “PL-480.”

“For the most part, the books that came through the PL-480 program are still available in South Asia. But preservation is often a challenge due to white ants, pests, and lack of temperature control and In contrast, most materials in the West remain well preserved thanks to the preservation and conservation efforts of our libraries,” says Michelson-Ambelang.

Ananya Vajpayee

Ananya VajpayeeAnother reason Michelson-Ambelang calls Western libraries colonial archives “is in part because they serve scholars, often excluding those outside their institutions. While librarians understand the disparities in access to South Asian materials , copyright laws limit sharing, reinforcing these gaps.”

So what happened when the PL-480 program ended?

Nye says the end of the program in the 1980s shifted the financial burden onto American libraries. “Libraries in the United States have had to pay for the selection, acquisition, compilation and delivery of resources,” he said. For example, the University of Chicago now spends more than $100,000 a year purchasing books and periodicals through the Library of Congress. field office in Delhi.

Vajpeyi believes the books-for-grains deal had a positive outcome. He studied Sanskrit, but his research at the University of Chicago spanned Indian and European languages (French, German, Marathi, and Hindi) and touched on linguistics, literature, philosophy, anthropology, and more. “At the Regenstein Library, I never failed to find the books I needed or get them quickly if they weren’t already there,” he says.

“Books are safe, valued, accessible and used. I have visited libraries, archives and institutions in all parts of India and the history in our country is universally depressing. Here they were lost, destroyed, neglected or very often made inaccessible. “