Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

It was declared the year of democracy. With more than a billion and a half votes cast in 73 countries, 2024 provided a rare opportunity to take the social and political temperature of nearly half the world’s population.

The results are in, and they deliver a shocking verdict on public office holders.

An incumbent in each of the 12 developed western countries holding national elections in 2024 has lost a share of the vote in the election, the first time this has happened in nearly 120 years of modern democracy. In Asia, even the powerful governments of India and Japan did not escape the evil spirit.

In spite of the situation or otherwise, centrists were often the losers when the voters threw behind the strong partisan parties. The populist right in particular advanced, driven largely by a positive shift among young people.

The results paint a picture of an angry electorate battered by high inflation, frustrated by the economic downturn, frustrated by rising immigration, and increasingly disillusioned by system as a whole.

In a way, the year of democracy produced the cry that democracy is no longer working, and the new generation, many of whom are voting for the first time, are giving a strong critique against the establishment.

On average across the developed worldthe electorate’s share of the vote has fallen by seven percent in 2024, an all-time record and more than double the decline in voters beating elected officials after the global financial crisis.

Many countries producing similar results point to the same situation, and inflation is the obvious cause.

Heading into 2024, high and rising prices were a top public concern in many states going to the polls. While recessions are not widely loved, their effects are not unevenly distributed. Inflation hurts everyone.

But if the cost of the health crisis acted as a deterrent for those in positions, a closer look at different countries and regions shows that it was the only driver of discontent.

The furor against the sitting government has reached Britain, where the Conservatives’ charge sheet has included not only high prices but also a corruption scandal, a crisis in the delivery of public health care, a self-inflicted economic crisis and a sharp rise in immigration.

Across the French channel, President Emmanuel Macron’s attempt to curb the populist right by calling snap legislative elections was criticized. The resulting political upheaval was yet to be fully resolved months later.

In India, Narendra Modi’s powerful Bharatiya Janata Party has scored a narrow victory but has lost its majority in parliament, struggling to stem the tide of discontent over growing divisiveness. strong economy and low job creation.

This was particularly pronounced among the youth, whose unemployment rate rose to nearly 50 percent before the election, according to data from the Indian Economic Observatory.

Even the exceptions to the anti-labor wave are not surprising when viewed in light of some of the central themes of the year’s political changes.

In Mexico and Indonesia respectively, Claudia Sheinbaum and Prabowo Subianto each improved on the margin of the sitting president. In both cases, they ran extensive campaigns promising to continue with their anti-elite predecessors, marking the closest majority win in twelve months. the past. Prabowo also relied heavily on the management of the new social media landscape, another common theme.

Globally, the weak performance of the major parties and the march of popular figures, especially on the right, was a strong theme as the anti-authoritarian wave, perhaps stronger .

Even the victory of the Labor party in Britain is not an exception here, as it won this year with fewer votes than in the last two elections it lost. And a few months after the big victory, the mood has turned against the party and the leader.

The French public’s outcry against Macron and his main party, meanwhile, reflects a worldwide sense of disillusionment with the political establishment, and the idea that. elected officials maybe they don’t know or don’t care what ordinary people think.

Although it ultimately fell short of the victory it had hoped for, the 15-point margin achieved by France’s Rassemblement National in the parliamentary elections was the largest recorded by any party in any developed country. this year. The second, third and fourth biggest gains of the year were made by the far-right in the form of Austria’s Freedom party, UK’s British Reform and Portugal’s Chega.

This speaks to the fact that immigration has been an increasing problem throughout the developed world in recent years, and was one of the most important issues on the minds of voters as they went to the polls.

Where conservative parties lost ground, it was generally the right-wing parties that were the main beneficiaries. The success of Nigel Farage’s Reform UK in wiping out Conservative voters in Britain is largely due to their failure to deliver on their promise to reduce immigration.

But the success of the anti-establishment was not limited to the right. The UK’s Greens were one of the most powerful extremist parties to re-emerge as voters disenchanted with the old establishment split on both sides.

While the timing and magnitude of the anti-establishment wave has led to short-term shocks of higher prices, the populist movement looks like a continuation — or perhaps an acceleration. method that has been playing in an increasing number of countries for at least two decades.

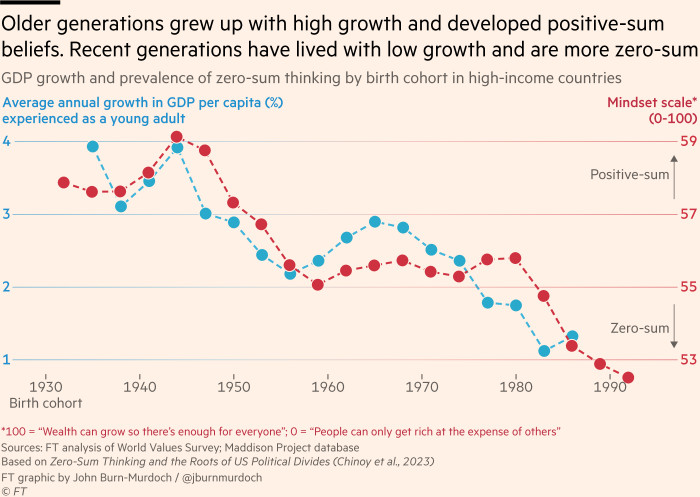

One prominent theory as to why we see this happening was presented with a strong influence paper published earlier this year by a group of Harvard economists, who found that people who grow up against a backdrop of low economic growth and low intergenerational development, are more likely to perceive the world as zero, where one person’s profit should accrue to another person. cost.

A steady decline in upward economic mobility rich countries therefore it may explain the extent of the rise of this sentiment, viz tend to associate with support for parties and politicians on the left and right who promise to dismantle the existing system or defend against external threats.

Another chance is that the dramatic changes in the media landscape over the past two decades have contributed to the elimination of long-standing attitudes against human speech and rhetoric. The emergence of social media has made it possible for people outside of politics to speak directly to the public, leveling the playing field that was previously biased towards celebrities and parties.

Beneath the surface of the results of the headlines, one of the most striking trends seen in many countries has been the rise of support for the populist right among young people.

In Britain, support for Reform is now higher among men in their teens and early twenties than among those in their thirties, and the perceived gender gap has widened among the youngest voters. A very similar pattern can be seen in the US, where young men also swung heavily to Donald Trump in November, and a similar pattern is emerging across Europe.

Importantly, there seems to be plenty of room for this trend to continue: the proportion of people who say they would vote for the extreme right is higher than they already are.

Such a clear change is surprising, but has no logical explanation. If dissatisfaction with the economic recession makes people no longer exist, few groups have had such problems as young people, whose economic conditions were there. steady decline across the west.

But it’s not just young men who have gone too far. Young women in the US also turned to Trump, while in the UK they turned more to the Greens.

This is consistent with research from polling company FocalData earlier this year, which found young people are more likely than their elders to support the country’s conservative party, and 2020 study which found satisfaction with democracy in the developed west falling faster and faster among young adults than any other group.

All shows are like that Two defining trends of 2024 are expected to continue next year. Recent polls show the incumbent governments of Australia, Canada, Germany and Norway are all on the verge of losing power in the coming months.

And in most of these countries it is the populist right that also looks set to make the biggest gains. A famous Norwegian A celebration of progress is currently leading after finishing fourth in 2021, and Germany’s AfD is currently polling in second place.

The crisis of hyperinflation may be over, but with stubborn economic growth, a widening wealth gap and a fragmented media, 2024 may prove to be an even more uncertain tipping point. one that is active on the lower levels.