Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

CNRLI

CNRLIWith his leopard-like spots, Navarro, a male lynx, screams during mating season as he walks toward a camera trap.

Just under 100 cm (39 in) long and 45 cm high, the Iberian lynx is a rare species. But there are now more than 2,000 in the wild in Spain and Portugal, so you are much more likely to see them than 20 years ago.

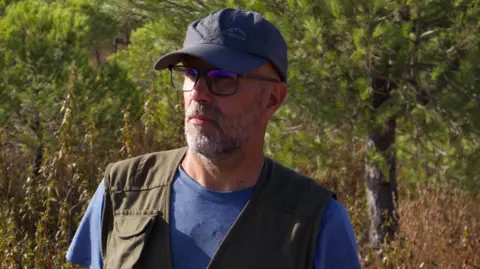

“The Iberian lynx was very, very close to extinction,” says Rodrigo Serra, who directs the breeding program in Spain and Portugal.

At the lowest point there were fewer than 100 lynxes left in two non-interacting populations, and only 25 of them were females of reproductive age.

“The only feline species that was threatened at this level was the saber-toothed tiger thousands of years ago.”

The decline in the lynx population was partly due to increasing land use for agriculture, an increase in road deaths and the fight for food.

Wild rabbits are essential prey for the lynx and two pandemics caused a 95% drop in their numbers.

In 2005, Portugal no longer had any lynxes left, but it was also the year in which Spain saw the first litter born in captivity.

It took another three years before Portugal decided on a national conservation action plan to save the species. In Silves, in the Algarve, a National Breeding Center for Iberian lynxes was built.

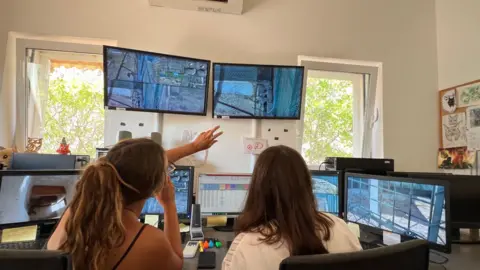

Here they are monitored 24 hours a day. The goal is twofold: prepare them for life in the wild and pair them for reproduction.

Serra speaks in a whisper, because even from a distance of 200 m can cause stress to the animals in the 16 pens where most of the animals are kept.

Sometimes, however, stress is exactly what bobcats need.

BBC/Antonio Fernandes

BBC/Antonio Fernandes“When we notice a litter getting a little more confident, we go in, chase them and make noise so they get scared again and climb the fences,” Serra says. “We are training them not to approach people in the wild.”

This is partly for their own protection, but also to keep them away from people and their animals. “A lynx should be a lynx, not treated like a domestic cat.”

That is why lynxes never associate food with people, but rather feed through a system of tunnels in the center.

Then, when the time comes, they are released into the wild.

Genetics determines where they end up, to reduce the risks of inbreeding or disease. Even if a lynx were born in Portugal, it could be brought to Spain.

Pedro Sarmento is responsible for the reintroduction of the lynx in Portugal and has been studying the Iberian lynx for 30 years.

“As a biologist, there are two things that strike me when I handle a lynx. It is an animal with a rather small head compared to its body and extraordinarily wide legs. This gives them a momentum and ability to jump that is rare.”

The breeding program and the return of the lynx have been hailed as great successes, but as their numbers increase, problems can also arise.

As lynxes in Portugal are usually released on private land, the organizers of the breeding program must first reach an agreement with the owners.

BBC/Antonio Fernandes

BBC/Antonio FernandesWhere the animals go is up to them, and although there have been some attacks on chicken coops, Sarmento says there haven’t been many.

“This can cause unrest among locals. We have been strengthening the cooperatives so that the lynxes cannot access them and, in some cases, we continue to monitor the lynxes and chase them away if necessary.”

It tells the story of Lítio, one of the first lynxes released in Portugal.

For six months Lítio remained in the same area but then the team lost track of him.

He finally arrived at Doñana, a national park in southern Spain where he had originally come from.

As Lítio was ill, he was treated and then returned to the breeding team in the Algarve.

A few days after leaving the center he began to return to Doñana, swimming across the Guadiana River to reach Spain.

For a while he disappeared, but was eventually brought back to the Algarve.

BBC/Antonio Fernandes

BBC/Antonio FernandesWhen he was released for the third time, Lítio did not venture back to Spain, but instead walked 3 kilometers, found a female, and never moved again.

“He is the oldest lynx we have here and since then he has fathered many cubs,” says Sarmento.

Three decades after Spain decided to save the lynx, the species is no longer in danger and Sarmento hopes it will reach a favorable conservation status by 2035.

For that to happen, the number must reach 5,000-6,000 in the wild.

“I saw how the species disappeared. It’s surreal that we are in a place where we can see lynxes in the wild or through camera traps almost daily,” says Sarmento.

The playback team is not being accommodating and there are risks involved in their work. Last year 80% of lynx deaths occurred on roads.

For now, however, they are confident that the Iberian lynx has been saved.