Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

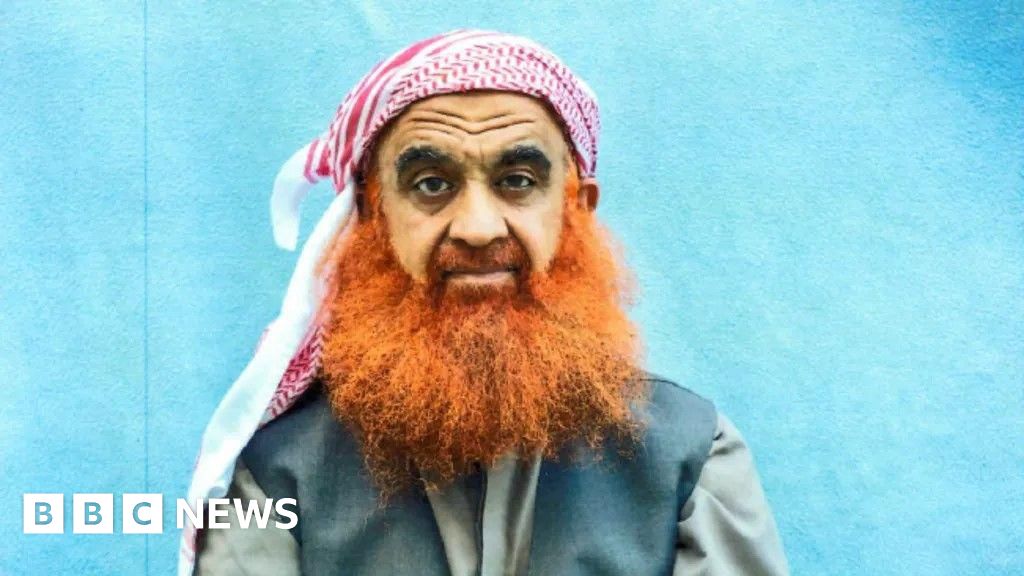

Photo courtesy of Khalid Sheikh Mohammed’s legal team

Photo courtesy of Khalid Sheikh Mohammed’s legal teamSitting in the front row of a war court at the US naval base at Guantanamo Bay in Cuba, Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, one of the world’s most famous defendants, appeared to be listening intently.

“Can you confirm that Mr. Mohammed pleads guilty to all charges and specifications without exceptions or substitutions?” —the judge asked his lawyer as Mohammed watched.

“Yes, we can, Your Honor,” the lawyer responded.

Sitting in court, Mohammed, 59, with his beard dyed bright orange and dressed in a headdress, tunic and trousers, bore little resemblance to a photograph. circulated shortly after his capture in 2003.

Mohammed, the accused mastermind of the 9/11 terrorist attacks in the United States, was due to plead guilty this week, more than 23 years after nearly 3,000 people were killed in what the US government has described as “the deadliest criminal act.” atrocious in history. American soil in modern history.

But two days later, just as Mohammed was preparing to formally present his decision – the product of a controversial agreement he reached with US government prosecutors – he instead watched silently as the judge said that the proceedings had been suspended under the orders of a federal appeals court. court.

It was expected to be a historic week for a case that has faced a decade of delays. Now, with a new complication, it continues towards an uncertain future.

“It will be an eternal trial,” said the relative of one of the 9/11 victims.

Mohammed has previously said that he planned “Operation 9/11 from A to Z,” conceiving the idea of training pilots to fly commercial airliners into buildings and taking those plans to Osama bin Laden, leader of the Islamist militant group al-Al Qaeda.

But he has not yet been able to formally admit his guilt in court. This week’s pause comes amid a dispute over an agreement reached last year between US prosecutors and his legal team, under which Mohammed would not face a death penalty trial in exchange for his guilty plea.

The United States government has spent months tried to terminate the agreementsaying that allowing the deal to go forward would cause “irreparable” harm to both him and the American public. Supporters of the deal see it as the only way forward in a case that has been complicated by the torture Mohammed and others faced in U.S. custody and questions about whether it tainted evidence.

After a last-minute appeal by prosecutors, a three-judge panel of the federal appeals court asked for the delay to give them time to consider the arguments before making a decision.

But the victims’ families had already traveled on a weekly flight to the base to watch the depositions in a gallery, where thick glass separated them and members of the press from the rest of the sprawling high-security room.

fake images

fake imagesAttendees had won their place at this week’s event through a lottery system. They arranged childcare and paid for kennels so they could care for their pets, knowing they could cancel their service at any time. On Thursday night, while speaking to the media at a base hotel, they learned that the pleas would no longer go forward.

Elizabeth Miller, whose father, New York City firefighter Douglas Miller, was killed in the attacks when she was six, said she was in favor of the agreement moving forward to “give it finality,” but acknowledged there were other issues. families who felt that way. It was too lenient.

“What’s so frustrating is that every time this goes back and forth, each camp gets their hopes up and then crushes them again,” he said, as other family members nodded in agreement.

“It’s like a perpetual limbo… It’s like a constant whiplash.”

This week’s pause is just the latest in a series of delays, complications and controversies at the base, where the US military has held detainees for 23 years.

The military prison at Guantanamo Bay was established during the “war on terrorism” that followed the 9/11 attacks that Mohammed is accused of orchestrating. The first detainees were taken there on January 11, 2002.

Then-President George Bush had issued a military order establishing military tribunals to try non-U.S. citizens, saying they could be held without charge indefinitely and could not legally challenge their detention.

Dressed in bright orange jumpsuits, the 20 men were taken to a temporary detention camp called X-Ray, where exposed cells, cages and beds with mats on the floor.

The camp, surrounded by barbed wire, has long been abandoned and overgrown: Weeds grow on the wooden guard towers and signs along the fence read “forbidden” in red text.

While conditions have improved at Guantánamo, it continues to face criticism from the United Nations and human rights groups over its treatment of detainees. And it continues to defy U.S. officials and advocates who hope to see it shut down.

As president, Barack Obama promised to close the prison during his term, saying it was contrary to American values. These efforts were revived under the Biden administration.

fake images

fake imagesUnlike Muhammad, most of the people held there since its creation were never charged with a crime.

The current detention centers are off-limits to journalists and only those with security clearance are allowed access.

Within a short drive there is an Irish pub, a McDonald’s, a bowling alley, and a museum that serves military personnel and base contractors, most of whom have never been inside the prison area.

As legal teams, journalists and families gathered at the base for Mohammed’s scheduled pleas, an early morning secret operation was carried out to remove a group of 11 Yemeni detainees from the base for resettlement in Oman .

With that move, the base, which once housed nearly 800 detainees, now has just 15, the lowest number in its history.

Of those remaining, all but six have been charged or convicted of war crimes, and lawyers plead their cases in complex legal battles in the base’s high-security courts.

When the court was dismissed on Friday, the judge said Mohammed’s pleas, if allowed to go forward, would now fall to the next US administration.