Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Astronomers have detected a mid-infrared flare from the supermassive black hole at the center of the Milky Way galaxy for the first time, shedding new light on the complex physics driving these energetic explosions.

The flare—a burst of energy that changes in intensity when the black hole’s magnetic field lines interact—fills in a field of black hole observations that previously eluded scientists. However, questions remain about the chaotic environment near the heart of the abyssal object.

The team’s flare detection and modeling is accepted for publication in the journal Astrophysical Journal Letters and does currently available arXiv on the preprint server. The findings were presented today at the 245th meeting of the American Astronomical Society in National Harbor, Maryland.

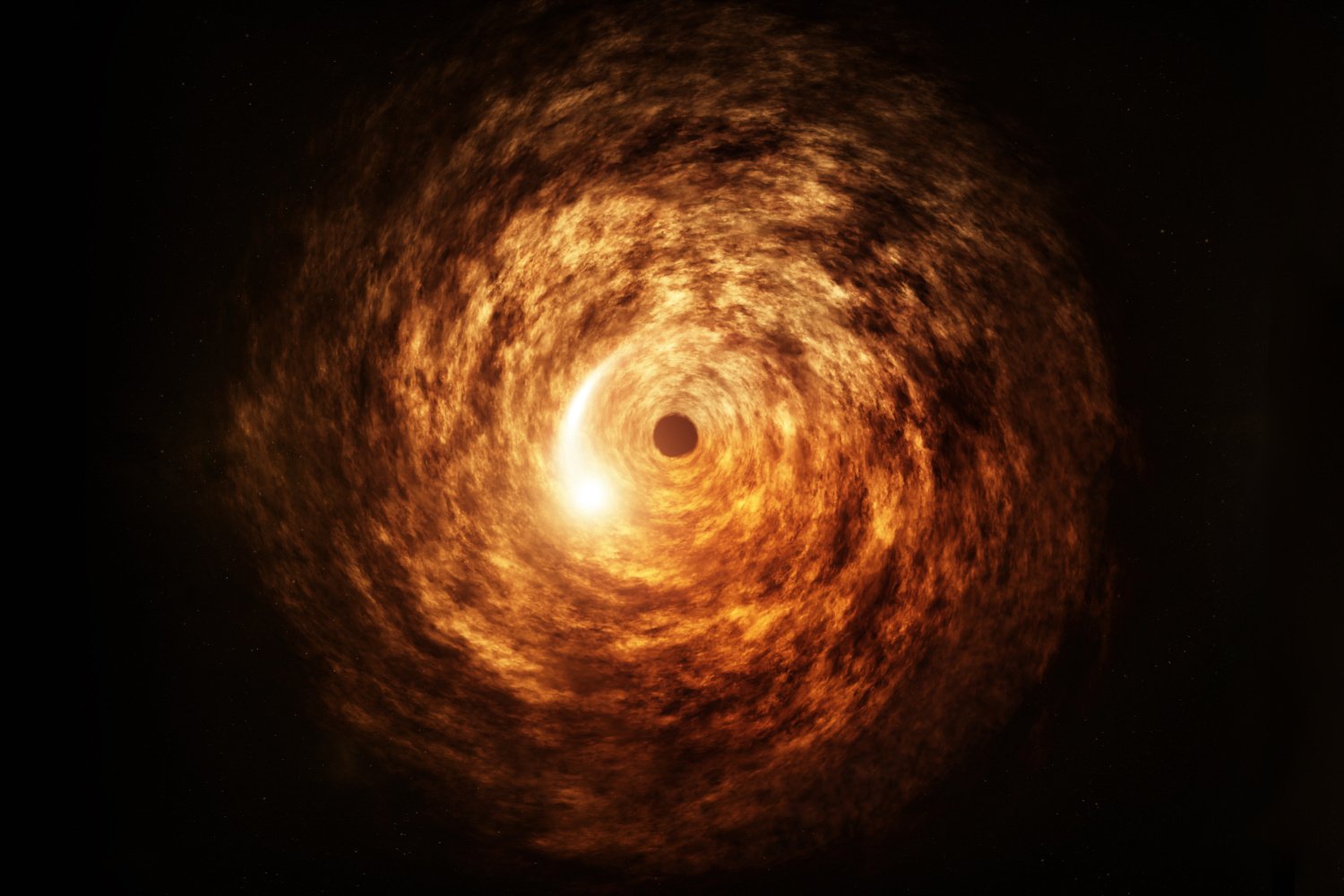

A black hole called Sagittarius A* (pronounced A-star) is an object about four million times the mass of our Sun, located at the core of the Milky Way. Black holes are ultra-dense objects with gravitational fields so strong that no light can escape beyond a point called the event horizon. In the artist’s conception at the beginning of this article, a black hole is a dark abyss at the core of a vortex of material.

“For more than 20 years, we’ve known what happens in the radio and Near Infrared (NIR) bands, but the relationship between them has never been 100% clear,” he said. Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory, part of the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard and the Smithsonian, in one center release. “This new observation in the middle of the MN fills this gap.”

Mid-infrared light has longer wavelengths than visible light, but shorter wavelengths than radio waves. It is also one of the specialties of the Webb Space Telescope, which the telescope takes with its Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI).

Cooling electrons in the black hole’s accretion disk—the superheated, glowing matter surrounding the object—release energy to power the flares. The role of electrons in black hole flares was detected at mid-infrared wavelengths and, according to Mikhail, provide another piece of evidence for what lights the flares.

The discovery and the team’s model provide greater clarity and complexity to the portrait of our galaxy’s central black hole. Modeling black hole physics and direct imaging of objects go hand in hand in bringing us closer to understanding the physics underlying some of the most massive and remarkable objects in our universe.

The Event Horizon Telescope Collaboration took direct images of the black hole for the first time in April 2019; cooperation continued with this feat first direct view Sagittarius A* in May 2022, although last year a group of researchers described flawed.

Last year, the telescope produced the highest-resolution observations of the planet ever made by a collaborative network of radio telescope observatories around the world. The work showed that future images of black holes at certain wavelengths could be 50% sharper than previously published images.

More observations may be needed to verify that cooling, high-energy electrons are indeed responsible for the flames. But the finding offers a new twist on the tale of black holes and demonstrates the role the Webb Space Telescope can play in hiding massive objects.