Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

If tattoos tend to fade within a person’s lifetime, imagine the wear and tear on the tattoos of 1,200-year-old mummies.

For the first time, an international team of researchers has used lasers to detect tattoos on mummies from Peru. The use of this technique is described in detail on January 13 to learn published in the magazine PNASresearchers have uncovered beautiful intricate designs and (literally) shed light on the intricate tattooing practices of the ancient Chancai culture. Their findings reveal a higher level of artistic skill in pre-Columbian Peru than previously thought.

Tattoos have existed as a form of artistic expression for over 5,000 years The oldest example belongs to the famous Iceman OtziHe died in 3300 in the Alps between Austria and Italy. However, because ancient soft-tissue remains are rare and tattoos fade and bleed over time—a condition made worse by the body’s decay after death—archaeologists have little opportunity to study the ancient art form. In opportunities that have presented themselves, researchers have historically used infrared imaging to analyze designs, but it still can’t reveal the finer details of tattoos, according to the study.

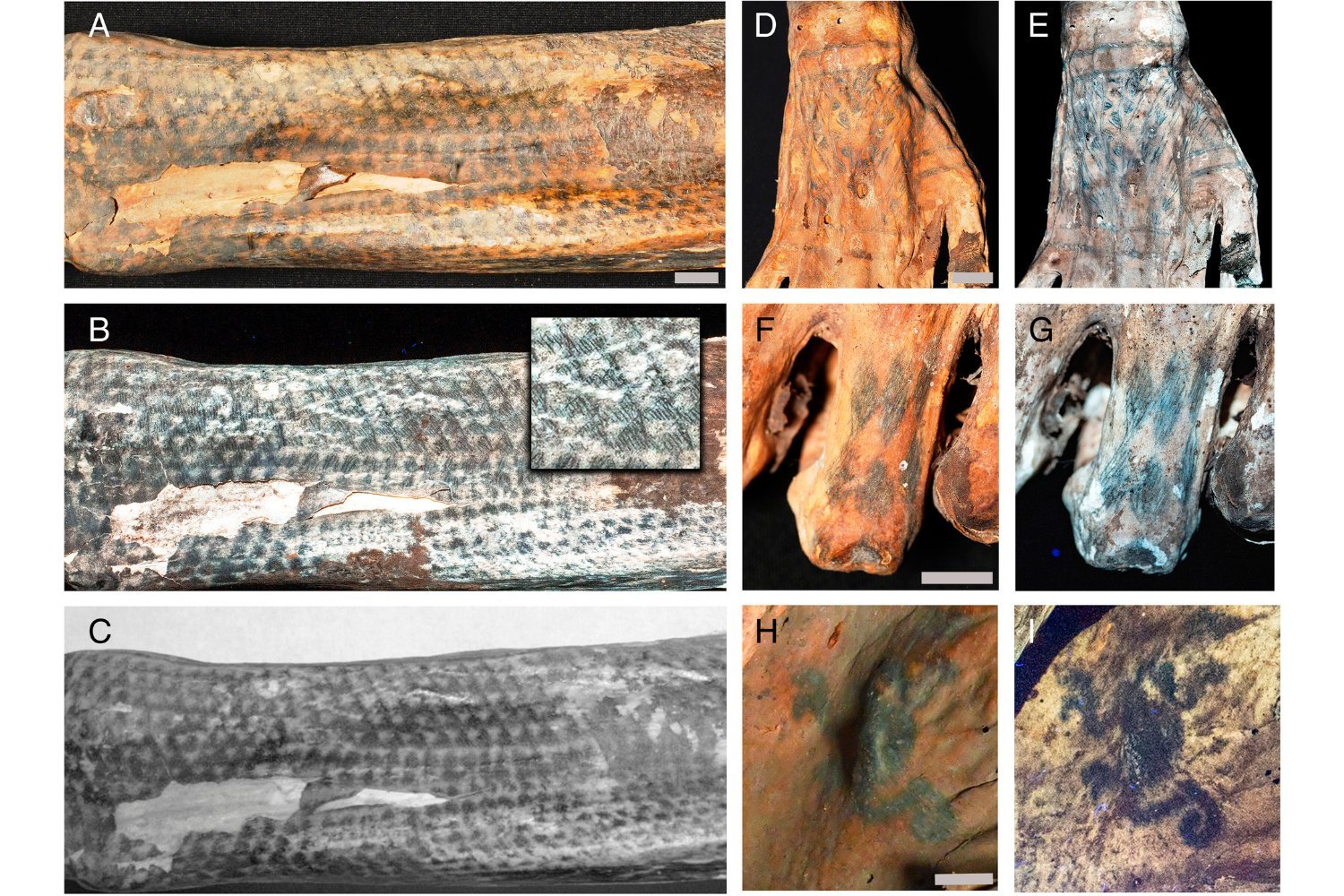

More recently, a team used a technique called laser-stimulated fluorescence (LSF), which uses lasers to reveal details of soft tissue, to study the tattoos of Peruvian mummies. Paleontologists have used LSF for years to study dinosaur fossils Science Alerthowever, this is the first time the technique has been used to analyze ancient tattoos on mummified human remains, and the results were fantastic.

“We’re basically turning the skin into a light bulb,” said Thomas G. Kaye of the Arizona-based nonprofit Foundation for the Advancement of Science, which participated in the study. Associated Press. In other words, the researchers used lasers to make non-tattooed skin glow dramatically differently than tattooed skin, revealing subtle ink designs invisible to the naked eye.

Researchers, including a scientist at the National University of Peru, José Faustino Sánchez Carrion, studied more than 100 approximately 1,200-year-old mummified human remains belonging to the Chancay culture. According to the study, the Chancay are a pre-Columbian people who lived on the central coast of present-day Peru between 900 and 1533 AD. Now known for their textiles, they eventually became part of the Inca Empire.

Although most of the tattoos on the Chancay mummies were “amorphous patches with poorly defined edges,” some designs had lines between 0.0039 and 0.0079 inches (0.1 to 0.2 millimeters) thick, the researchers found in the study. These details “reflect the fact that each ink dot was deliberately placed by hand with great skill, creating a variety of subtle geometric and zoomorphic patterns,” they added. “We can assume that this technique involved a finer-pointed object than the standard No. 12 modern tattoo needle, probably a single cactus needle or a sharpened animal bone based on known materials that the artists had at hand.”

The researchers then compared the tattoo designs to other Chancay material culture, including pottery, weaving, and rock art, and determined that the tattoos were the culture’s “most complex art” found to date.

“The study therefore reveals a higher level of artistic sophistication in pre-Columbian Peru than previously appreciated, extending the degree of artistic development currently found in South America,” the researchers explained.

Perhaps this first successful use of LSF to study tattoos on mummies will lead to the discovery of more ancient designs that will give modern tattoos a run for their money.