Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

nilupero

niluperoNiluper says she has been living in agony.

As a Uyghur refugee, she spent the last decade waiting for her husband to join her and their three children in Türkiye, where they now live.

The family was detained in Thailand in 2014 after fleeing growing repression in their hometown in China’s Xinjiang province. She and the children were allowed to leave Thailand a year later. But her husband remained detained, along with 47 other Uighur men.

Niluper (not her real name) now fears that she and her children will never see him again.

Ten days ago, he learned that Thai officials had tried to persuade detainees to sign consent forms to be sent back to China. When they realized what was on the forms, they refused to sign them.

The Thai government has denied having any immediate plans to return them. But human rights groups believe they could be deported at any time.

“I don’t know how to explain this to my children,” Niluper told the BBC in a video call from Türkiye. His children, he says, continue to ask about their father. The youngest has never met him.

“I don’t know how to digest this. I live in constant pain, in constant fear that at any moment I could receive the news from Thailand that my husband has been deported.”

He The last time Thailand deported Uyghur asylum seekers. It was in July 2015. Without warning, he put 109 of them on a plane back to China, sparking a storm of protests from governments and human rights groups.

The few photographs released show them hooded and handcuffed, guarded by a large number of Chinese police. Little is known about what happened to them after their return. Other deported Uighurs have received long prison sentences in secret trials.

The nominee for Secretary of State in the incoming Trump administration, Marco Rubio, has vowed to pressure Thailand not to send back the remaining Uyghurs.

One human rights defender has described their living conditions as “hell on earth”.

They are all being held at the Immigration Detention Center (IDC) in central Bangkok, which houses most of those charged with immigration violations in Thailand. Some are there only briefly, while they wait to be deported; others stay there much longer.

Driving along the narrow, congested road known as Suan Phlu, it’s easy to miss the nondescript group of concrete buildings, and it’s hard to believe that they house some 900 detainees; Thai authorities do not give precise figures.

The IDC is known to be a hot, overcrowded and unhealthy place. Journalists are not allowed to enter. Lawyers often warn their clients to avoid being sent there if possible.

fake images

fake imagesThere are 43 Uyghurs there, in addition to five others held in a Bangkok prison for trying to escape. They are the last of around 350 who fled China in 2013 and 2014.

They are kept isolated from other inmates and are rarely allowed visits from outsiders or lawyers. They have little opportunity to exercise or even see the light of day. They have not been charged with any crime, other than entering Thailand without a visa. Five Uyghurs have died in custody.

“The conditions there are appalling,” says Chalida Tajaroensuk, director of the People’s Empowerment Foundation, an NGO trying to help the Uyghurs.

“There is not enough food, it is mostly soup made with cucumber and chicken bones. It is crowded there. The water they receive, both for drinking and washing, is dirty. They are only provided with basic medicines and these are inadequate.” If someone gets sick, it takes a long time to get a doctor’s appointment. And due to dirty water, hot weather and poor ventilation, many Uyghurs suffer from rashes or other skin problems.”

But the worst part of their detention, say those who have experienced it, is not knowing how long they will be imprisoned in Thailand and the constant fear of being sent back to China.

Niluper says there were always rumors about the deportation, but it was difficult to find out more. Escaping was difficult because they had children with them.

“It was horrible. We were so scared the whole time,” Niluper remembers.

“When we thought about being sent back to China, we would have preferred to die in Thailand.”

China’s repression against Uyghur Muslims has been well documented by the UN and human rights groups. Up to a million Uyghurs are believed to have been detained in re-education camps, in what human rights advocates say is a state campaign to eradicate Uyghur identity and culture. There are many accusations of torture and forced disappearances, which China denies. He says he has been running “vocational centers” focused on deradicalizing Uyghurs.

Niluper says she and her husband faced hostility from Chinese state officials because of their religiosity: her husband was an avid reader of religious texts.

The couple made the decision to flee when people they knew were being arrested or missing. The family was part of a group of 220 Uighurs who were caught by Thai police trying to cross the border into Malaysia in March 2014.

fake images

fake imagesNiluper was detained in an IDC near the border, and then in Bangkok, until she, along with 170 other women and children, was allowed in June 2015 to go to Turkey, which normally offers asylum to Uyghurs.

But her husband is still at the IDC in Bangkok. They were separated when they were detained and she has had no contact with him since a brief meeting they were allowed in July 2014.

She says she was one of 18 pregnant women and 25 children crammed into a room just four by eight metres. The food was “bad and there was never enough to go around.”

“I was the last to give birth, at midnight, in the bathroom. The next day the guard saw that my condition and that of my baby was not good, so they took us to the hospital.”

Niluper was also separated from her eldest son, who was only two years old at the time and was being held with his father, an experience she says has traumatized him, after experiencing “terrible conditions” and witnessing a guard beating a recluse. When the guards took him away, she says, he didn’t recognize her.

“I was so scared, screaming and crying. I couldn’t understand what had happened. I didn’t want to talk to anyone.”

It took him a long time to accept his mother, he says, and then he did not abandon her for a moment, even after arriving in Türkiye.

“It took him a long time to understand that he was finally in a safe place.”

Thailand has never explained why it will not allow the remaining Uyghurs to join their families in Türkiye, but it is almost certainly due to pressure from China.

Unlike other inmates at the IDC, the Uyghurs’ fate is handled not by the Immigration Department but by Thailand’s National Security Council, a body chaired by the prime minister in which the military has significant influence.

fake images

fake imagesAs the influence of the United States, Thailand’s oldest military ally, declines, that of China has been steadily increasing. The current Thai government is interested in building even closer ties with China to help revive the faltering economy.

The United Nations Refugee Agency has been accused of doing little to help the Uyghurs, but it says it has no access to them so it can’t do much. Thailand does not recognize refugee status.

However, pandering to China’s desire to bring back the Uyghurs is not without risks. Thailand just took a seat on the UN Human Rights Council, so it lobbied hard.

Deporting 48 men who have already endured more than a decade of imprisonment would seriously tarnish the image the Thai government is trying to project.

Thailand will also be aware of what happened just a month after the last mass deportation in 2015.

On August 17 of that year. A powerful bomb exploded at a shrine in Bangkok which was popular with Chinese tourists. Twenty people were killed, in what was widely assumed to be retaliation by Uyghur militants, although Thai authorities sought to downplay the link.

Two Uyghur men were charged with the attack, but their trial has lasted nine years with no end in sight. One of them, their lawyers say, is almost certainly innocent. A veil of secrecy surrounds the trial; The authorities seem reluctant to let anything come to light from the hearings linking the bomb to the deportation.

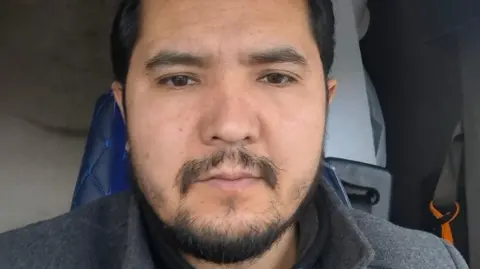

Hassan Magnet

Hassan MagnetEven those Uyghurs who have managed to reach Turkey must contend with their uncertain status there and the disruption of all communications with their families in Xinjiang.

“I haven’t heard my mother’s voice in 10 years,” says Hasan Imam, a Uighur refugee who now works as a truck driver in Türkiye.

He was in the same group as Niluper captured on the Malaysian border in 2014.

He recalls how the following year Thai authorities misled them about their plan to deport some of them to China. He says they were told some men would be moved to a different facility because the one they were in was too full.

This was after some women and children were sent to Turkey and, unusually, men in the camp were also allowed to speak on the phone to their wives and children in Turkey.

“We were all happy and full of hope,” says Hassan. “They were selected one by one. At that time they had no idea that they would be sent back to China. Only later, through an illicit phone we had, did we discover from Turkey that they had been deported.”

This filled the remaining detainees with despair, Hasan recalls, and two years later, when he was temporarily transferred to another detention camp, he and 19 others made a notable exhaustusing a nail to make a hole in a crumbling wall.

Eleven were recaptured, but Hasan managed to cross the forested border into Malaysia and from there reached Turkey.

“I don’t know what condition my parents are in, but for those still detained in Thailand it is even worse,” he says.

They fear being returned and imprisoned in China, and they also fear that this will mean harsher punishment for their families, he explains.

“The mental stress for them is unbearable.”