Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Russia Editor, Minsk Reports

Reuters

ReutersThere are times in history when countries are caught by election fever.

January 2025 in Belarus is not one of them.

Drive around Minsk and you won’t see large billboards promoting portraits of candidates.

There is little campaign.

The gray skies and sleet of a Belarusian winter add to a primal sense of inactivity.

And inevitability.

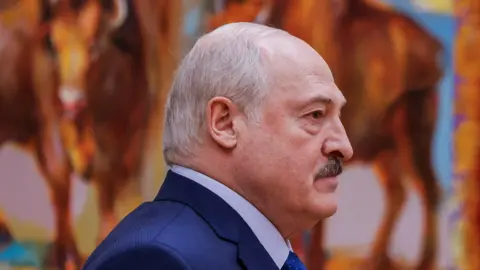

The outcome of the 2025 presidential election is not in doubt. Alexander Lukashenko, once dubbed “Europe’s last dictator” who ruled Belarus with an iron fist for more than 30 years, will be declared the winner and secure a seventh term in office.

Its supporters call it an exercise in “Belarusian democracy.” Your opponents Reject the process as “a farce.”

Even Mr. Lukashenko himself claims to lack interest in the process.

“I’m not following the election campaign. I don’t have time,” the Belarusian leader told workers at the Minsk car plant this week.

The workers presented him with a gift: an ax for cutting wood.

“I will try before the elections,” Mr. Lukashenko promised, to rapturous applause.

Four and a half years ago, at a different company, Belarus’s leader received a much cooler reception.

A week after the 2020 presidential elections, Alexander Lukashenko visited the Minsk Wheels tractor plant. The leaked video showed that he was mocked and deviled by the workers. They shouted “”Go away! Go away! “.

In 2020, the official election result, 80% for Mr. Lukashenko, had sparked anger and large protests across the country. Belarusians poured into the streets to accuse their leader of stealing their votes and the elections.

In the brutal police crackdown that followed, thousands of anti-government protesters and critics were arrested. Eventually, the wave of repression extinguished the protests and, with Russia’s help, Mr. Lukashenko clung to power.

The United Kingdom, the European Union and the United States refuse to recognize him as the legitimate president of Belarus.

Alexander Lukashenko’s strongest opponents (and potential rivals) are in prison or have been forced into exile.

That is why this week the European Parliament passed a resolution calling on the EU to reject the upcoming presidential election as “a farce” and pointing out that the election campaign has been brought to “minimum standards for democratic elections.”

Memory Interviewing Alexander Lukashenko last Octoberthe day the date of the presidential elections was announced.

“How can these elections be free and democratic if the opposition leaders are in prison or abroad?” I asked.

“Do you really know who the opposition leaders are?” Mr. Lukashenko responded.

“An opposition is a group of people who should serve the interests of at least a small number of people in the country. Where are these leaders you talk about? Wake up!”

Alexander Lukashenko is not the only candidate. There are four others. But they seem more like spoilers than serious challengers.

I drive four hours from Minsk to meet one of them. Sergei Syrankov is the leader of the Communist Party of Belarus. In the city of Vitebsk I sit at one of his campaign events. In a large room, Mr. Syrankov addresses a small audience, flanked by his group’s emblem, the hammer and sickle.

His campaign slogan is unusual to say the least: “Not instead of, but together with Lukashenko!”

He is a presidential candidate who openly supports his opponent.

“There is no alternative to Alexander Lukashenko as the leader of our country,” Syrankov tells me. “So, we are participating in the elections with the president’s team.”

“Why do you think there is no alternative?” Asked.

“Because Lukashenko is a man of the people, a man of the soil, who has done everything to make sure that we don’t have the kind of chaos that they have in Ukraine.”

“You’re fighting for power, but you support another candidate. That’s… unusual,” I suggest.

“I am sure that Alexander Lukashenko will win a thumping victory. But even if he wins and I don’t, the communists will be the winners,” Mr. Syrankov responds.

“The main communist in our country is our head of state. Lukashenko still has his old membership card from the Soviet Communist Party days.”

Also on the ballot is Oleg Gaidukevich, leader of the right-wing Belarusian Liberal Democratic Party. He’s also not racing to win.

“If someone dares to suggest the outcome of the elections, it is unknown, they are a liar,” Gaidukevich tells me.

“It is obvious that Lukashenko will win. He has a massive rating…we will fight to strengthen our positions and prepare for the next elections.”

Mr Lukashenko’s critics reject the claim that his popularity is “massive”. But there is no doubt that he has support.

On the edge of Vitebsk is the small town of Oktyabrskaya. Talking to people there, I detect concern that a change in leadership could lead to instability.

“I want a stable salary, stability in the country,” Sergei tells me. “Other candidates make promises, but they may not keep them. I want to keep what I have.”

“The situation today is very tense,” says Zenaida. “Maybe there are other people worthy of power. But by the time a younger leader gets his feet under the desk, he makes those important connections with other countries, and with his own people that will take a long time.

“God forbid, we should end up like Ukraine.”

Today in Belarus there is fear of instability, fear of the unknown and fear of the government. They all work in favor of Alexander Lukashenko.