Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Middle East Analyst of the BBC

Reuters

ReutersHistoric buildings in Mosul, including churches and mosques, are being reopened after years of devastation resulting from the acquisition of the Iraqi city by the extremist group of the Islamic State (IS).

The project, organized and financed by UNESCO, began a year after IS was defeated and expelled from the city, in northern Iraq, in 2017.

UNESCO General Director Audrey Azoulay, and Iraqi Prime Minister, Mohammed Shia ‘Al-Sudani, attend a ceremony on Wednesday to mark reopening.

Local artisans, residents and representatives of all Mosul’s religious communities will also be there.

In 2014, Mosul is busy, which for centuries was seen as a symbol of tolerance and coexistence between different religious and ethnic communities in Iraq.

The group imposed its extreme ideology in the city, attacking minorities and killing opponents.

Three years later, a coalition backed by the United States in alliance with the Iraqi army and the militias linked to the State set up an intense offensive of land and air to snatch the city back is control. The bloodiest battles focused on the old city, where the group fighters did a last position.

Mosul’s photographer, Ali Al-Barodi, recalls the horror that received it when he first entered the area shortly after the battle of the street in the summer of 2017 was over.

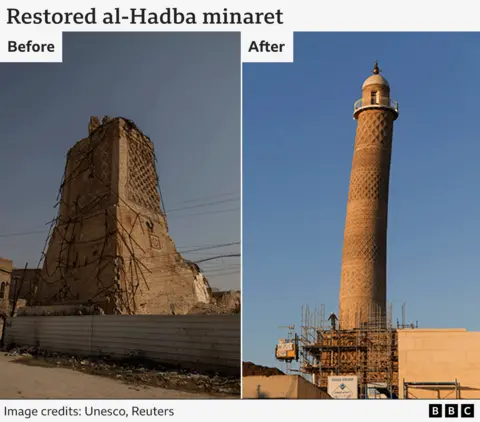

He saw the gloriously biased Al-Hadba Minaret, known as the “hunchback”, who had been emblematic of Mosul for hundreds of years, in ruins.

“It was like a ghost town,” he says. “Dead body everywhere, a disgusting smell and horrible scenes of the city and the horizon without the hebba mine.

“It was not the city we knew, it was like a metamorphosis, which we never imagined even in our worst nightmares. I was silent after that for a couple of days. I lost my voice. I lost my head.”

The eighty percent of the old city of Mosul, on the west shore of the Tigris, was destroyed during the three -year occupation of IS.

It was not only the churches, mosques and ancient houses that should be repaired, but also the community spirit of those who had lived there for so long in relative harmony between religions and ethnicities.

The great task of rebuilding began under the auspices of UNESCO with a budget of $ 115 million (£ 93 million) that the agency had managed to wobble, much of the United Arab Emirates and the European Union.

Father Olivier Poquillon, a Dominican priest, returned to Mosul to help supervise the restoration of one of the key buildings, the notre convent -Dame de l’here, known locally as a -saa’a, which was founded almost 200 years.

“We start trying first to gather the team, a team composed of people from old Mosul from different denominations, Christians, Muslims who work together,” he says.

Father Poquillon says that gathering communities was the greatest challenge and the greatest achievement.

“If you want to rebuild the buildings that you have first to rebuild confidence: if you do not rebuild trust, it is useless to rebuild the walls of those buildings because they will become a goal for other communities.”

In charge of the entire project, which included the restoration of 124 old houses and two especially fine mansions, it has been the main architect Maria Rita Aceoso, who arrived in Mosul directly from the restoration work for UNESCO in Afghanistan.

“This project shows that culture can also create jobs, can promote skills development and, in addition, it can make those involved feel part of something significant,” she says.

She hopes that reconstruction can restore hope and allow the recovery of the identity and cultural memory of people.

“I think this is particularly important for young generations that grow in a situation of conflict and political instability,” he adds.

UNESCO says that more than 1,300 local young people have been trained in traditional skills, while some 6,000 new jobs have been created.

More than 100 classrooms were renewed in Mosul. Thousands of historical fragments were recovered and cataloged from the rubble.

Among the large number of engineers involved in reconstruction, 30% were women.

Eight years later, the bells are sounding again through Mosul from the church of Al-Tahera, whose roof collapsed after the serious damage under the occupation of IS in 2017.

Other important Mosul reference points have also been restored, which twisting mine from Al-Hadba, the Dominican convent Al-Saa’a and the complex of the Al-Nouri mosque.

And people have been able to return to the houses that have been home to their families for centuries.

A resident, Mustafa, said: “My house was built in 1864, unfortunately it was partly destroyed during Mosul’s release and it was not appropriate to live there, especially with my children.

“So I decided to move to my parents’ house. I was very happy and excited to see my house rebuilt again.”

EPA

EPAAbdullah’s family has also lived in a house in the old city since the nineteenth century, when the area was a center for wool trade, so he says that his home is so precious to them.

“After UNESCO rebuilt my house, I returned,” he says. “I can’t describe the feeling I had because after seeing all the destruction that happened there, I thought I could never return and live there again.”

The scars of what the people of Mosul endured have not healed, as well as much of Iraq remains in a fragile state.

But the rebirth of the old city of the rubble represents the hope of a better future, since Ali al -Baroodi continues to document the evolution of his beloved home day by day.

“It’s really like seeing a dead person returning to life in a very, very beautiful way, that is the true spirit of the city that returns to life,” he says.