Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Business Reporter

Gonzalo Rojas

Gonzalo RojasA proposed law in the Colombia Congress seeks to prohibit the sale of merchandise held by former drug trafficker Pablo Escobar. But opinions are divided into it.

On Monday, November 27, 1989, Gonzalo Rojas was in school in the Colombian capital of Bogotá when a teacher took him out of class to deliver some devastating news.

His father, also called Gonzalo, had died in a plane crash that morning.

“I remember gone and see my mother and my grandmother waiting for me, crying,” says Rojas, who was only 10 years old at that time. “It was a very, very sad day.”

Minutes after takeoff, an explosion aboard Avianca Flight 203 killed the 107 passengers and crew, as well as three people on the ground who were run over by the fall of rubble.

The explosion was not an accident. It was a deliberate bomb attack by Pablo Escobar and his Medellín poster.

While one was defined by drug wars, bombings, kidnappings and a murder rate with a sky have been largely relegated to Colombia’s past, Escobar’s legacy has not done so.

The notorious criminal, who was killed by security forces in 1993, has achieved a state almost like worship worldwide, immortalized in books, music and television productions such as the Netflix Narcos series.

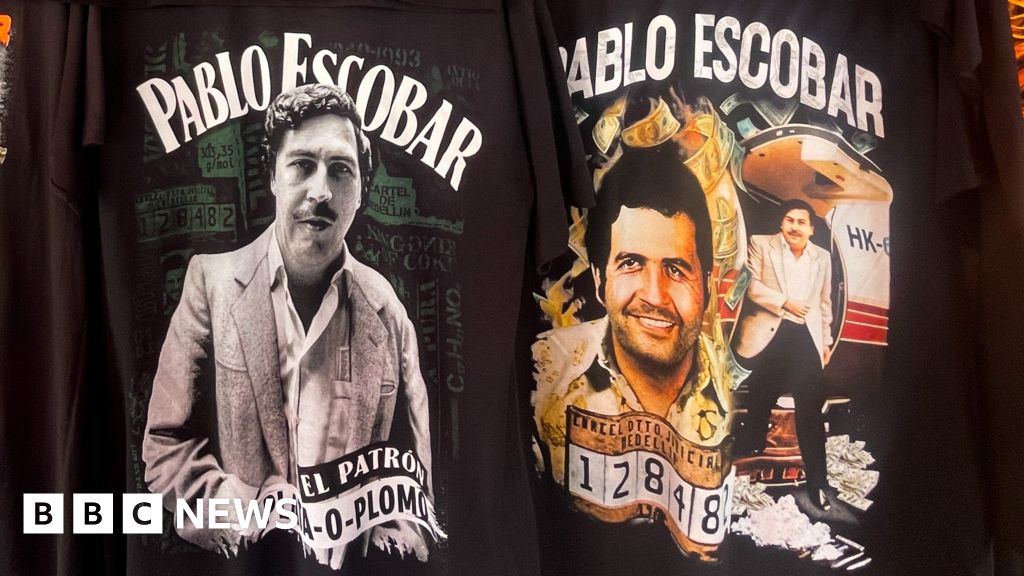

In Colombia, its name and face are adorned in cups, keys and t -shirts in tourist shops that mainly serve curious visitors.

But a proposed law in the Colombia Congress seeks to change this.

The bill wants to prohibit Escobar’s merchandise, and that of other convicted criminals, to help end the glorification of a drug chief who was central to the world trade in cocaine and widely responsible for at least 4,000 murders.

“The difficult problems that are part of the history and memory of our country cannot be remembered simply by a shirt, or a sticker sold in a corner,” says Juan Sebastián Gómez, a member of the Congress and co -author of the bill.

The proposed law would prohibit the sale, as well as the use and transport of clothing and items that promote criminals, including Escobar. It would mean fines for those who violated the rules and a temporary suspension of companies.

Catherine Ellis

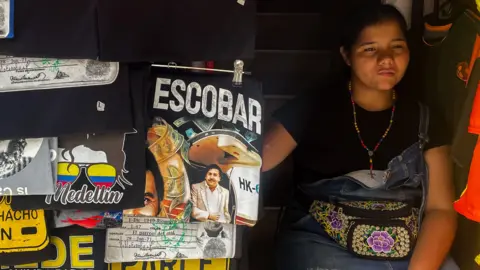

Catherine EllisMany suppliers that sell the goods affirm that a law that prohibits this merchandise would damage their livelihoods.

“This is terrible. We have the right to work, and these T -shirts of Paul sell especially well,” says Joana Montoya, owner of a position full of merchandise Escobar in commune 13, a popular tourist area of Medellín.

Medellín, the hometown of Escobar, was known as “the most dangerous city in the world” at the end of the 80s and early 90s due to violence associated with drug wars and the armed conflict of Colombia.

Today it has been revitalized in an innovation and tourism center, with sellers anxious to take advantage of the influx of visitors who want to take houses home, some related to Escobar.

“This merchandise of Escobar benefits many families here: it supports us. It helps us to pay our rental, buy food, take care of our children,” says Mrs. Montaya, who supports herself and her little daughter.

Mrs. Montoya says that at least 15% of her sales come from Escobar products, but some vendors tell the BBC that for them it is up to 60%.

Catherine Ellis

Catherine EllisIf the bill is approved, there would be a defined period of time for sellers to become familiar with the new rules and eliminate their Escobar actions.

“We would need a transition phase so that people can stop selling these products and replace them with others,” explains Congressman Gómez. He says that Colombia has more interesting things than showing than drug traffickers, and that the association with Escobar has stigmatized the country abroad.

Some of the shirts, sold for around £ 5, carry a phrase linked to Escobar: “Silver or lead?” This symbolizes the choice that the head of the poster gave to those who represented a threat to their criminal operations: accept a bribe or be killed.

The assistant of the María Suárez store believes that the profits obtained from the sales of Escobar merchandise are not ethical.

“We need this prohibition. He did horrible things and these memories are things that should not exist,” he says, explaining that he feels uncomfortable that his boss wares the Escobar articles.

It was believed that Escobar and his Medellín poster had at one time controlled 80% of the cocaine that entered the United States. In 1987, he was appointed one of the richest people in the world by Forbes magazine.

He spent part of his fortune developing private neighborhoods, but many people consider this as a tactic to buy loyalty of some segments of the population.

Years after his father’s death, Mr. Rojas remembers him as a quiet and responsible man, who loved his family. For him, the bill is a decisive moment.

“It is a milestone on the way on how we reflect on what is happening in terms of marketing Pablo Escobar to correct it,” says Mr. Rojas.

However, he has criticism about the proposals. He believes that the bill does not focus enough on education.

Juan Sebastián Gómez

Juan Sebastián GómezRojas remembers many years ago when he met a man with a green shirt with a Silhouette of Escobar, and the words “Pablo, president”.

“It caused me so much confusion that I could not tell him anything about it,” he says.

“There must be more emphasis on how we deliver different messages to the new generations, so that there is no positive image of what a poster chief is.”

Rojas has actively participated in efforts to remodel the narratives around Escobar and drug trafficking. Together with some other victims, Narcostore.com launched in 2019, an online store that seems to sell Escobar theme articles.

But none of the products really exists and when customers select an article, a victim’s video testimony is shown. Rojas says that the site has attracted 180 million visits around the world.

In the Colombia Congress, the bill faces four stages that must be approved before it can become law. Gómez says he hopes to display the reflection both inside and outside the Congress.

“In Germany you don’t sell Hitler t -shirts or swastikas. In Italy you don’t sell Mussolini stickers, and you don’t go to Chile and get a copy of the Pinochet identification card.

“I think the most important thing that the bill can do is generate a conversation as a country, a conversation that has not yet happened.”

The mayor of Medellín, who was also a presidential candidate in the 2022 elections, has publicly supported the bill, calling for the merchandise “an insult to the city, the country and the victims.”

In the town, a luxury area of Popular Medellín among tourists, three Americans sail for a position full of memories. One buys a lid with the name and face of Escobar printed on the front. He says he wants a memory of “history.”

But for supporters of the bill, it is not about eliminating Escobar from history, it is about erasing a mythical construction from it, promoting new ways to honor the victims that he killed, and recognizing the persistent pain of the victims left back.