Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Climate researcher and the environment

Getty images

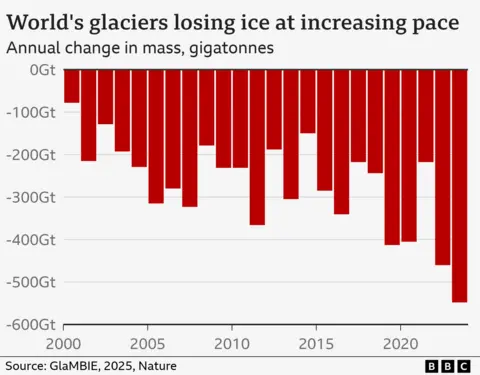

Getty imagesThe glaciers of the world are melting faster than ever under the impact of climate change, according to the most complete scientific analysis to date.

Mountain glaciers – frozen ice rivers – act as a fresh water resource for millions of people around the world and enclose enough water to raise world levels of the sea in 32 cm (13 inches) if they were completely melted.

But since the change of the century, they have lost more than 6,500 billion tons, or 5%, their ice.

And the fusion rhythm is increasing. During the last decade more or less, glacier losses were more than a third higher than during the 2000-2011 period.

The study combined more than 230 regional estimates of 35 research teams worldwide, which makes scientists even safer about how the glaciers melt and how they will evolve in the future.

Glaciers are excellent indicators of climate change.

In a stable climate, they remain approximately the same size, winning so many ice through snowfall as they lose by merger.

But glaciers have been reduced almost everywhere in the last 20 years as temperatures have increased due to human activities, mainly burning fossil fuels.

Between 2000 and 2023, glaciers outside the main ice sheets in Greenland and Antarctica lost around 270 billion tons of ice a year on average.

These numbers are not easy to understand. Then, Michael Zemp, director of the World Monitoring Service of Glacier and main author of the study, uses an analogy.

The 270 billion tons of ice lost in a single year “corresponds to consumption (of water) of the entire world population in 30 years, assuming 3 liters per person and day,” he told BBC News.

The exchange rate in some regions has been particularly extreme. Central Europe, for example, has lost 39% of its glacier ice in just over 20 years.

The novelty of this study, Posted in Nature magazineIt is not so much to discover that glaciers are melting faster and faster, we already knew. Instead, its strength lies in gathering evidence of the entire research community.

There are several ways to estimate how glaciers are changing, from field measurements to different types of satellite data. Each has their own advantages and disadvantages.

Direct measurements about glaciers, for example, provide very detailed information, but are only available for a small fraction of the more than 200,000 glaciers worldwide.

By systematically combining these different approaches, scientists can be much safer about what is happening.

These estimates of the community “are vital since they give confidence to people to make use of their findings,” said Andy Shepherd, head of the Department of Geography and Environment of the University of Northumbria, who was not the author of the recent study.

“That includes other climatic scientists, governments and industry, in addition, of course, any person who is concerned about the impacts of global warming.”

Glaciers take the time to respond completely to a changing climate, depending on their size, anywhere between a few years and many decades.

That means they will continue melted in the coming years.

But, crucially, the amount of ice lost by the end of the century will depend largely on the amount of humanity that continues to heating the planet by releasing carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases.

This could be the difference between losing a quarter of the world’s glacier ice, if global climatic objectives are met, and almost half if the heating continues without control, the study warns.

“Every tenth part of a degree of warming that we can avoid will save some glaciers and save us from a lot of damage,” said Professor Zemp.

These consequences go beyond local changes to landscapes and ecosystems, or “what happens in the glacier does not stay there,” as Professor Zemp expresses.

Hundreds of millions of people worldwide depend to some extent on the seasonal fusion water of glaciers, who act as giant deposits to help damp the drought populations. When the glaciers disappear, so do their water supply.

And there are also global consequences. Even seemingly small increases to the world sea level, from mountain glaciers, the main ice sheets in Greenland and Antarctica, and the warmest oceanic waters that occupy more space, can significantly increase the frequency of coastal floods.

“Every centimeter of the increase in sea level exposes another 2 million people to annual floods somewhere on our planet,” said Professor Shepherd.

The world levels of the sea have already increased by more than 20 cm (8 inches) since 1900, with about half of that since the early 1990s, and faster increases are expected in the coming decades.