Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Technology reporter

HELEN GEBREGIORGIS

HELEN GEBREGIORGISIn Washington DC and its surroundings, volunteers and activists have been walking through the streets and houses to see how healthy the air is.

They are armed with industry grade monitors that detect the presence of several gases. The devices look a bit like Walkie-Talkies.

But they are equipped with sensors that reveal the scope of methane, turning this invisible gas into specific numbers on a screen.

Those numbers can be worrisome. In a period of 25 hours, neighborhood researchers found 13 Outdoor methane leaks at concentrations that exceed the lower explosive limit. They have also found methane leaks within households.

A key concern has been health. Methane and other gases, especially nitrogen oxide of gas stoves, are linked to greater risks of asthma.

Djamila Bah, a medical care worker, as well as a tenant leader for the action of the community organization in Montgomery, reports that one in three children has asthma in homes tested by the organization.

“It is very heartbreaking and alarming when you are doing the tests and then you discover that some people live in that condition that they cannot change for now,” says Bah.

Methane can be a danger to human health, but it is also powerful greenhouse gas.

While it has a much shorter useful life in the atmosphere than carbon dioxide (CO2), methane is much better to catch heat and explains approximately a room of the increase in global temperature from industrialization.

Methane emissions come from a diverse variety of sectors. The main one is fossil fuels, waste and agriculture.

But methane is not always easy to notice.

It can be detected using portable gas sensors such as those used by community researchers. It can also be visualized using infrared cameras, since methane absorbs infrared light.

Monitoring can be based on the ground, including devices mounted on the vehicle or antenna, including drone -based measurement. Combining technologies It is especially useful.

“There is no perfect solution,” says Andreea Calcan, programs management officer at the Methane Emissions International Observatory, an UN initiative.

There are compensation between the cost of technologies and the analysis scale, which could be extended to thousands of facilities.

Fortunately, he has seen an expansion of affordable methane sensors in the last decade. Therefore, there is no reason to wait to monitor methane, on any scale. And the world needs to address the small leaks and high -emitting events, she says.

Carbon mapping

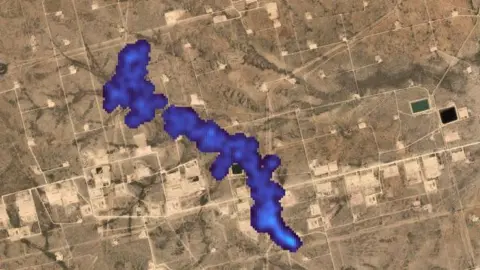

Carbon mappingOn a larger scale, satellites are often good in identifying the supermitters: Less frequent but mass emitters, such as huge oil and gas leaks. Or they can detect smaller and more widespread emitters that are much more common, such as cattle farms.

Current satellites are generally designed to monitor an issuer scale, says Riley Duren, CEO of The Carbon Mapper, a non -profit organization that tracks emissions.

He compares this with filmar cameras. A telephoto lens offers a greater resolution, while a large angle lens allows a larger field of vision.

With a new satellite, the carbon mapper focuses on high resolution, high sensitivity and rapid detection, to detect more precision the emissions of supermitters. In August 2024, Carbon Mapper launched the Tanager-1 satellite, together with the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory and the Earth Plannet Labs image company.

Carbon mapping

Carbon mappingSatellites have struggled to detect methane emissions in certain environments, such as poorly maintained oil wells in snowy areas with a lot of vegetation. Low light, high latitudes, mountains and areas on the high seas also have challenges.

Mr. Duran says that high-resolution Tanager-1 can respond to some of these challenges, for example, essentially slipping by the gaps through the gaps on the cloud cover or forest coverage.

“In an oil and gas field, the high resolution could be the difference between isolating the methane emissions of an oil well of an adjacent pipe,” he says. This could help determine exactly who is responsible.

Carbon Mapper began to release emission data, based on the observations of Tanager-1, in November.

It will take several years to build the complete constellation of satellites, which will depend on financing.

Tanager-1 is not the only new satellite with an approach to methane data delivery. Methanesat, a project of the Environmental Defense Fund and private and public partners, was also launched in 2024.

With the growing sophistication of all these satellite technologies, “what was previously invisible is now visible,” Duran says. “As a society, we are still learning about our true footprint of methane.”

It is clear that better information about methane emissions is needed. Some energy companies have tried to evade methane detection through the use of “closed fuels” to obscure gas bankruptcy.

Translating knowledge to action is not always simple. Methane levels continue to increaseeven as the information available too.

For example, the methane alert and response system (Mars) uses satellite data to detect methane emissions notifies companies and governments. The Mars team gathered a large number of methane plume images, verified by humans, to train an automatic learning model to recognize such feathers.

In all places that Mars constantly monitors, according to its emission history, the model verifies a methane plume every day. Analysts then examine any alert.

Because there are many locations to be monitored, “this saves us a lot of time,” says Itziar Iraqulis Loitxate, the remote control lead for the International Observatory of Methane emissions, which is responsible for Mars.

In the two years since its launch, Mars has sent more than 1,200 alerts for higher methane leaks. Only 1% of those have led to answers.

However, Mrs. Iraqulis is still optimistic. Some of those alerts led to direct actions, such as repairs, including cases in which emissions ceased despite the fact that the oil and gas operator did not officially provide comments.

And communications are improving all the time, says Mrs. Irakulis. “I hope that this 1%, let’s see that it grows a lot in next year.”

At the community level, it has been powerful for residents, such as those of the Washington DC area, taking air pollution readings and using them to counteract erroneous information. “Now that we know better, we can do better,” says Joelle Novey about interreligious power and light.