Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

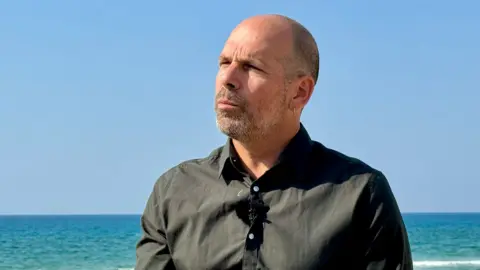

Middle East correspondent

Ore Ruthy Field / BBC

Ore Ruthy Field / BBCWhen Dawn approached on the morning of October 7, 2023, many of the attendees of the Nova Music Festival festival near the Gaza border took illegal recreational drugs such as MDMA or LSD.

Hundreds were high when, shortly after dawn, Hamas’ gunmen attacked the site.

Now the neuroscientists who work with festival survivors say that there are early signs that MDMA, also known as ecstasy or Molly, may have provided some psychological protection against trauma.

Preliminary results, currently reviewed by pairs in order to publication in the coming months, suggest that the drug is associated with more positive mental states, both during the event and in later months.

The study, conducted by scientists from the University of Haifa in Israel, could contribute to a growing scientific interest in how MDMA could be used to treat psychological trauma.

It is believed that it is the first time that scientists have been able to study a mass trauma event where a large number of people were under the influence of drugs that alter the mind.

The Hamas gunmen killed 360 people and kidnapped more dozen at the festival site where 3,500 people had been partying.

“We had people who hid under the bodies of their friends for hours while in LSD or MDMA,” said Professor Roy Salomon, one of those who direct the research.

“There is talk that many of these substances create plasticity in the brain, so the brain is more open to change. But what happens if you support this plasticity in such a terrible situation? Will it be worse or better?”

The investigation tracked the psychological responses of more than 650 survivors of the festival. Two thirds of these were under the influence of recreational drugs, including MDMA, LSD, marijuana or psilocybin, the compound found in hallucinogenic fungi, before the attacks occurred.

“MDMA, and especially MDMA that was not mixed with anything else, was the most protective,” the study found, according to Professor Salomon.

He said that those in MDMA during the attack seemed to face much better mentally in the first five months later, when a lot of processing occurs.

“They were sleeping better, they had less mental anguish, they were doing better than the people who did not take any substance,” he said.

The team believes that pro -social hormones caused by drugs, such as oxytocinIt helps to promote union: it helped reduce fear and increase the feelings of camaraderie among those fleeing from the attack.

And even more important, they say, it seems to have left the survivors more open to receive the love and support of their families and friends once they were at home.

Clearly, the investigation is limited only to those who survived the attacks, which makes it difficult to determine with certainty if specific drugs helped or hindered the exhaust possibilities of the victims.

But the researchers found that many survivors, such as Michal Ohana, firmly believe that he played a role, and say that belief itself can help them recover from the event.

“I feel he saved my life, because I was very high, as if he were not in the real world,” he told me. “Because regular humans can’t see all these things, it’s not normal.”

Without the drug, she believes that she would have frozen or collapsed on the floor, and that the gunmen have killed or captured.

Ore Ruthy Field / BBC

Ore Ruthy Field / BBCDoctors in several countries have already I experienced with MDMA -assisted psychotherapy for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSP) In a test environment – although Only Australia has approved as treatment.

The countries that have rejected it include the United States, where the food and medicines administration cited concerns about the design of studies, which treatment may not offer lasting benefits and about the potential risk of heart problems, injuries and abuses.

MDMA is classified as a class A drug in the United Kingdom, and has been related to liver, renal and cardiac problems.

In Israel, where MDMA is also illegal, psychologists can only use it to treat customers in an experimental research base.

The preliminary findings of the Nova study are being closely followed by some of those Israeli doctors who experience MDMA as a treatment for PTSD after October 7.

Dr. Anna Harwood-Gross, clinical psychologist and research director at the Metiv Psychorauma center in Israel, described the initial findings as “really important” for therapists like her.

He is currently experiencing with the use of MDMA to treat PTSD within the Israeli army, and had worried about the ethics of inducing a vulnerable psychological state in customers when there is a war.

“At the beginning of the war, we question if we could do this,” he said. “Can we give MDMA when there is a risk of a siren of air attacks? That will return to potentially traumatize them. This study has shown us that even if there is a traumatic event during therapy, the MDMA could also help process that trauma.”

EPA

EPADr. Harwood-Gross says that the first indications of therapeutic use of MDMA are encouraging, even among military veterans with chronic PTSD.

It has also altered old assumptions about the “rules” of therapy, especially the duration of the sessions, which must be adjusted when working with customers under the influence of MDMA, she says.

“For example, our thoughts on 50-minute therapy sessions have changed, with a patient and a therapist,” Dr. Harwood-Gross told me. “Having two therapists and long sessions, up to eight hours, is a new way of doing therapy. They are looking at people very integral and give them time.”

She says that this new longer format shows promising results, even without patients taking MDMA, with a 40% success rate in the placebo group.

Israeli society itself has also changed its trauma and therapy approach after the attacks of October 7, according to Danny Brom, founding director of the center of Psychotrauma Metiv at the Herzog hospital in Jerusalem, and a senior figure in the industry.

“It’s as if this were the first trauma we are happening,” he said. “I have seen wars here, I have seen many terrorist attacks and people said: ‘We don’t see trauma here.’

“Suddenly, there seems to be a general opinion that now everyone is traumatized and everyone needs treatment. It is an incorrect approach.”

What broke, he said, is the sense of security that many Jews believed that Israel would provide them. These attacks discovered a collective trauma, he says, linked to Holocaust and persecution generations.

Getty images

Getty images“Our story is full of massacres,” Psychologist Atzmon Meshulam told me. “As a psychologist now in Israel, we face the opportunity to work with many traumas that were not being treated previously, like all our narratives for 2,000 years.”

Collective trauma, combat trauma, drugs that alter the mind, sexual aggression, hostages, survivors, body colleagues, injured and duel: Israel’s trauma specialists face a complex problem of clients’ problems that are now flooded in therapy.

The scale of this mental health challenge is reflected in Gaza, where a large number of people have been killed, wounded or left without home after a devastating 15 month war, and where there are few resources to help a deeply traumatized population.

The war in Gaza, caused by Hamas attacks against Israeli communities in October 2023, was suspended in January in a six -week truce, during which Hamas Israeli hostages were exchanged by Palestinian prisoners in Israeli prisons.

But there is little sense on both sides that peace and security needed to begin to heal.

The truce expired last weekend, with 59 Israeli hostages still in captivity of Hamas. Many gazanes are waiting, with their full bags, so that war resumes.

Meanwhile, Nova’s survivor Michal Ohana says that over time, some hope that he has moved from attacks, but is still affected.

“I wake up with this, and I’m going to sleep with this, and people don’t understand,” he told me.

“We live this every day. I feel that the country supported us in the first months, but now after a year, they feel: ‘Ok, you must return to work, back to life.’ But we can’t.”

Additional reports from Oren Rosenfeld and Naomi Scherbel-Ball