Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Mark Wilberforce

Mark WilberforceWhen my mother told me at the age of 16 that we were going from the United Kingdom to Ghana during the summer holidays, I had no reason to doubt her.

It was just a fast trip, a temporary break, nothing to worry about. Or I thought so.

A month later, he dropped the bomb: I did not return to London until I reformed and had gained enough GCSE to continue my education.

They encaphed me similar to the British-Ghanaian adolescent who recently took his parents to the Superior Court of London for sending him to school in Ghana.

In his defense, they told the judge that they did not want to see their 14 -year -old son becoming “another black teenager stabbed to death in the streets of London.”

In the mid -1990s, my mother, primary school teacher, was motivated by similar concerns.

I had been excluded from two secondary schools in the Brent district in London, going out with the wrong crowd (becoming the wrong crowd) and a dangerous path.

My closest friends at that time ended up in prison due to armed robbery. If I had stayed in London, I would surely have been convicted with them.

But being sent to Ghana also felt as a prison sentence.

I can empathize to some extent with the adolescent, who said in his judicial statement that he feels “living in hell.”

However, speaking for myself, when I turned 21 I realized what my mother had done had been a blessing.

Unlike the child in the center of the case of the Court of London, who lost, I did not go to the boarding school in Ghana.

My mother placed me in the care of her two closest brothers, they wanted to monitor me and it was considered that being close to guests could be a great distraction.

First I stayed with my Uncle Fiifi, a former UN environmentalist, in a city called Dansoman, near the capital, Accra.

The change of lifestyle hit hard. In London, I had my own room, access to washing machines and a sense of independence, even if I was using it recklessly.

Getty images

Getty imagesIn Ghana, I was waking me at 05:00 to sweep the patio and wash my uncle’s muddy truck and my aunt’s car.

It was his vehicle that would later steal, a decisive moment.

I didn’t even know how to drive correctly, treating a manual as automatic and I blocked it in the Mercedes of a high -ranking soldier.

I tried to flee the scene. But that soldier caught me and threatened to take me to the Burma camp, the notorious military base where people had disappeared in the past.

That was the last truly reckless thing I did.

It wasn’t just the discipline I learned in Ghana, it was a perspective.

Life in Ghana showed me how much I had taken for granted.

Wash the clothes by hand and prepare meals with my aunt made me appreciate the necessary effort.

The food, like everything in Ghana, required patience. There were no microwave, or fast food races.

Making the traditional Mass Fufu dish, for example, is laborious and implies hitting cooked ñames or cassava in a paste with a mortar.

At that time, he felt like a punishment. Looking back, I was building resilience.

Initially, my uncles considered to put me in high-end schools such as the Ghana or SOS-HERMANN GMINER INTERNATIONAL COLLEGE SCHOOL.

But they were intelligent. They knew that a new team could form to cause chaos and pranks.

Instead, I received private registration at Accra Academy, a state high school to which my late father had attended. It meant that they often taught me on my own or in small groups.

Sulley Lansah

Sulley LansahThe lessons were in English, but outside the school that those around me often spoke local languages and it was easy for me to pick them up perhaps because it was such an immersive experience.

Back home in London, I loved learning bad words in my mother’s language, but I was far from fluid.

When I later moved to the subject city to stay with my favorite uncle, Uncle Jojo, an agriculture expert, continued private registration at the topic high school.

In contrast to the child who appears in the headlines in the United Kingdom, who affirmed that Ghana’s education system was not at standard, it seemed demanding.

They considered me an academic talent in the United Kingdom, despite my problematic forms, but in reality it was difficult for me to go in Ghana. The students of my age were far ahead in subjects such as Mathematics and Sciences.

The rigor of the Ghanaian system pushed me to study harder than ever in London.

The result? I obtained five GCSE with grades C and more, something that once seemed impossible.

Beyond academic achievements, the Ghanaian society instilled values that have stayed with me for life.

Respect for the elderly was not negotiable. In all the neighborhoods in which he lived, he greeted the elders than you, regardless of whether or not he knew them.

Ghana did not make me more disciplined and respectful, but made me brave.

Football played an important role in that transformation. I played in the parks, which were often hard red clay with stones and loose stones, with two square posts designed with wood and rope.

I was very far from the well -maintained releases in England, but it hardened me in a way that I could not have imagined, and it is not surprising that some of the best players seen in the English Premier League come from Western Africa.

Getty images

Getty imagesThe aggressive style played in Ghana was not only skill, but it was resistance and resistance. Being approached in a rough terrain meant getting up, dusting and continuing.

Every Sunday, I played football on the beach, although it would often be late because there was absolutely no way that none of my uncles would allow me to stay at home instead of attending the church.

Those services seemed that they lasted forever. But it was also a testimony of Ghana as a fearful nation of God, where faith is deeply rooted in everyday life.

The first 18 months were the most difficult. I was bothered by restrictions, tasks, discipline.

I even tried to steal my passport to fly back to London, but my mother was ahead of me and had hid it well. There was no escape.

My only option was to adapt. At some point, I stopped seeing Ghana as a prison and began to see her as a happy home.

I know some others like me who were sent back to Ghana by his parents living in London.

Michael Adom was 17 when he arrived at Accra for school in the 1990s, describing his experience as “bittersweet.” He stayed until 23 years old and now lives in London working as a probation officer.

His main complaint was loneliness: he missed his family and friends. There were moments of anger about their situation and the complications of feeling misunderstood.

This is largely due to the fact that his parents had not taught him or his brothers any of the local languages when they grew up in London.

“I did not understand Ga. I did not understand Twi. I did not understand Pidgin,” says the 49 -year -old man.

This made him feel vulnerable during his first two and a half years, and, according to him, his possibility of being silver, for example, by those growing prices because he seemed foreigner.

“Anywhere I went, I had to make sure to go with someone else,” he says.

But it ended fluently on Twi and, in general, believes that positive aspects surpassed the negatives: “A man made me.

“My experience of Ghana matured me and changed me for the better, helping me identify who I am, as Ghanaés, and consolidated my understanding of my culture, background and family stories.”

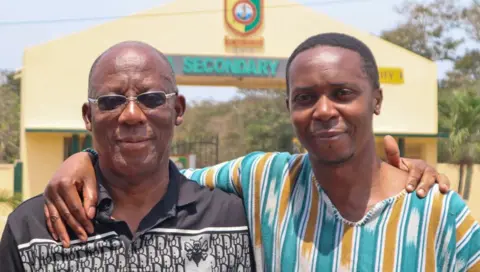

Mark Wilberforce

Mark WilberforceI can agree with this. In my third year, I had fallen in love with culture and even stayed for almost two more years after approving my GCSE.

I developed a deep appreciation of local food. Back in London, I never thought twice about what I was eating. But in Ghana, the food was not just sustenance, each dish had its own history.

I obsessed with “Waakye”: a dish made of rice and black -eyed peas, often cooked with millet leaves, giving it a distinctive purple brown color. In general, it was served with fried banana, the “shito” spicy black pepper sauce, boiled and sometimes even spaghetti or fried fish. It was the best comforting food.

I enjoyed the music, the warmth of the people and the meaning of the community. He was no longer “caught” in Ghana, he was thriving.

My mother, Patience Wilberforce, died recently, and with her loss I have deeply reflected on the decision she made so many years ago.

She saved me. If I did not fool me to stay in Ghana, the chances of having a criminal record or even fulfilling time in prison would have been extremely high.

I enrolled in the Northwest London school at age 20 to study the production and communications of the media, before joining BBC Radio 1xtra through a mentoring scheme.

The boys with whom it used to hang out in northwest London did not have the second chance I had.

Ghana reformed my mentality, my values and my future. He turned a wrong threat into a responsible man.

While such experience could not work for everyone, he gave me education, discipline and respect he needed to reintegrate in society when I returned to England.

And for that, I am always indebted to my mother, with my uncles and with the country that saved me.

Mark Wilberforce is an independent journalist based in London and Accra.

Getty Images/BBC

Getty Images/BBC