Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

BBC news

Entertainment of the plate

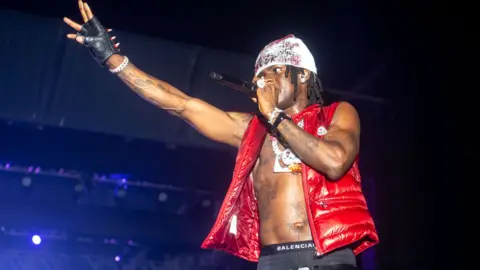

Entertainment of the plateThe scenes that are reproduced in Nigeria during holiday periods could be in a film: emotional meetings at the airport terminals, a champagne that flows like water in high -end clubs and Afrobeats artists from the list to dominate the stages for the public full throughout the country.

This is when Nigerians abroad return for a visit to the country of origin. They are nicknamed that I just returned (IJGB) and bring more than complete suitcases.

Their western accents enter and leave Pidgin, their wallets are driven by the exchange rate and its presence feeds the economy.

But an uncomfortable truth also stands out.

Those who live in Nigeria, who win in the local currency of Naira, feel closed from their own cities, especially in the Economic Center of Lagos and the Capital, abuses, as prices increase during festive periods.

Residents say that this is particularly the case of “Detty December”, a term used to send the celebrations around Christmas and New Year.

Detty Dicember makes lakes almost wireless for the locals: traffic is horrible, prices are infected and companies stop prioritizing their usual customers, a lake -based radio presenter tells the BBC.

The popular media personality asked not to be appointed to express what some might consider controversial opinions.

But he is not the only one who has these opinions and some are reflecting, with the Easter summer holiday season and the diaspora, whether IJGB are helping the division of Nigeria’s class or are making it even more broad.

“Nigeria is very classist. Ironically, we are a poor country, so it is a bit silly,” adds the radio presenter.

“The wealth gap is massive. It is almost as if we were separated.”

It is true that although Nigeria rich in oil is one of the largest economies in Africa and the most populous country on the continent, its more than 230 million citizens face great challenges and limited opportunities.

At the beginning of the year The Oxfam beneficial organization warned The wealth gap in Nigeria was reaching a “level of crisis.”

The statistics of 2023 are surprising.

According to the world inequality database, more than 10% of the population had more than 60% of Nigeria’s wealth. For those with jobs, 10% of the population took home 42% of income.

The World Bank says that the figure of those who live below the poverty line is 87 million. “The second largest poor population in the world after India”

AFP

AFPMartins Ifeanacho, a professor of sociology at the University of Port Harcourt, says that this resulting class division and division have grown since Nigeria’s independence from the United Kingdom in 1960.

“We have gone through so many economic difficulties,” the academic tells BBC, who returned to Nigeria after studying in Ireland in the 1990s.

It points to the finger to the greed of those who are in a position of political power, either at the federal or state level.

“We have a political elite that bases its calculations on how to acquire power, accumulate wealth in order to capture more power.

“Common people are out of the equation, and that is why there are many difficulties.”

But it’s not just about money in the bank account.

Wealth, real or perceived, can dictate access, state and opportunity, and the presence of the diaspora can magnify the class division.

“Nigeria’s class system is difficult to point out. It’s not just about money, it’s about perception,” explains the radio presenter.

It gives the example of going out to eat in lakes and how the peacock is so important.

In restaurants, those who arrive at a Range Rover are quickly attended, while those of a KIA can be ignored, says the radio presenter.

Social mobility is difficult when the richness of the nation remains within a small elite.

With probabilities stacked against those who try to climb the stairs, for many Nigerians, the only realistic road to a better life is to leave.

The World Bank blames the “creation of weak employment and business prospects” that suffocate the absorption of “3.5 million Nigerians who enter the workforce every year.”

“Many workers choose to emigrate in search of better opportunities,” he says.

Since the 1980s, middle -class Nigerians have sought opportunities abroad, but in recent years, urgency has intensified, especially between gene generation and millennials.

This mass exodus has been called “Japa”, a Yoruba word that means “escape.”

Getty images

Getty imagesA 2022 survey He discovered that at least 70% of Nigerian young people would move if they could.

But for many, leaving is not simple. Studying abroad, the most common route, can cost tens of thousands of dollars, not including travel, accommodation and visa expenses.

“Japa creates this aspirational culture where people now want to leave the country,” says Lulu Okwara, a 28 -year recruitment officer.

She went to the United Kingdom to study financing in 2021, and is one of the IJGB, since she returned to Nigeria at least three times since she moved.

Mrs. Okwara points out that in Nigeria there is a pressure to succeed. A culture where achievement is expected.

“It’s success or nothing,” he tells BBC. “There is no space for failure.”

This deeply integrated feeling makes people feel they should do anything to succeed.

Especially for those who come from more working class background. IJGB have a point to demonstrate.

“When people go out, their dream is always to return as heroes, mainly during Christmas or other festivities,” says Professor Ifeanacho.

“You return home and mix with your people you have lost for a long time.

“The type of welcome that will give you, the children who will run towards you, is something you love and appreciate.”

Success is pursued at any cost and putting a foreign accent can help him ascend on the social scale of Nigeria, even if he has not been abroad.

“People pretend accents to get access. The more you sound British, the greater their social status,” says Professor Ifeanacho.

Remember a story about a pastor who preached every Sunday on the radio.

“When they told me that this man had not left Nigeria, I said: ‘No, that is not possible.’ Because when you hear him speak, everything is American,” he says incredulously.

Getty images

Getty imagesAmerican and British accents, especially act as a different type of currency, softening paths in both professional and social environments.

The recoil in social networks suggests that some IJGB are in front: they can increase the adulation of the hero that returns, but in fact lacks financial influence.

Bizzle Osikoya, the owner of The Plug Entertainment, a business that houses live music events in West Africa, says he has found some problems that reflect this.

He tells the BBC about how several IJGB have attended their events, but they have tried to recover their money.

“They returned to the United States and Canada and put a dispute over their payments,” he says.

This may reflect the desperate effort to maintain a successful facade in a society where each wealth exhibition is analyzed.

It seems that in Nigeria, the performance is key, and the IJGB that they can presume can certainly climb the ladder of the class.

Getty Images/BBC

Getty Images/BBC