Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Fashion writer

Dastkari hates Samiti

Dastkari hates SamitiFor decades, Gamchha has been an ubiquitous presence in Indian streets.

The traditional scarf, made of a piece of red and white pictures, is used as a towel, pillow, turban, eye mask and even a shoulder curtain, mainly by working classes in the western flaw state and other regions of the country.

But an exhibition in the capital of India, Delhi, which ended two weeks ago, has highlighted the history of ordinary fabric in a unique way.

Titled Gamchha: From the ordinary to the extraordinary, he showed more than 250 pieces of the short cut of 14 Indian states to show the variations of the scarf in all regions.

From Gamchhas Blancos de Kerala with pencil -colored edges, Odisha’s kat fabrics to Assam’s “gamusa” cotton with red swans and large floral patterns, interpretations varied from being handmade by hand.

“The program is about talking about a symbol of social equality that the garment can evoke, even after decades of being out of the speech,” said textile expert Jaya Jaitly, founder of Dastkari Haat Samiti, a craft organization that presented this show.

The exhibition is part of a series of shows and efforts, held in recent months, which seek to redefine our understanding of Indian textiles taking it in new directions.

From rich woven silks, printed brocades and an intricate Chintz to a variety of less commented textiles, India’s contribution to the global textile industry is unique.

But despite the recognition, even in some of the largest museums in the world, its documentation has been exclusive and has not kept up to date with contemporary practices within the industry.

Until now.

Sustained by foundations for art and crafts and curated by researchers in collaboration with collectors and private museums, several new exhibitions are generating some rebirth within the industry.

Dastkari hates Samiti

Dastkari hates SamitiIt is a deviation from the most popular and glamorized version of fashion: there are no Bollywood stars that open the crowd that opens the show or the sponsored posterior parts. And the places are often far from the big cities.

On the other hand, the approach is to get away from urban designers, most of whom are trained in elite universities in India and abroad, and take local artisans directly to Redile.

These exhibitions are leading the “egalitarianism promised by technology” in the textile ecosystem, says Ritu Sethi, founder of the crafts of India Revival Trust. “Due to Instagram and other digital platforms, anonymity around artisans is also detaching,” she says.

What was once a small community of curators and customers, has now grown to include experts from several fields, including art and architecture.

Together, they want to take the history of textiles beyond their rich richness, associated with the greatness of the palaces and the fans of ceremonial rituals and weddings, to include various traditions of fabrics and the people behind it.

The sculpture of a more inclusive contemporary identity is, according to the acclaimed designer David Abraham, a return home and “a recovery of pride and value”.

“For the Indians, the relationship with textiles has depth depth. We express ourselves culturally through colors, fabrics and fabrics and each of these has an assigned meaning. These shows are reaffirming a value in our system,” he says.

Consider these instances. Bengal textiles: A shared legacy, in Kolkata until the end of March, highlights the historical uniqueness of the textile traditions of undivided Bengal.

On exhibition there are some fabrics and garments never seen before the seventeenth century so far. There are cotton saris and dhotis (curtains used by men) shown by the famous fabric traditions of the region such as Jamdani, which is still a fabric sought even today. Then, there are rare Indo -Portuguese and some Haji rumals: embroidered religious fabric once exported to Indonesia and parts of the Arab world as a headdress for men.

Weovers Studio Resource Center

Weovers Studio Resource CenterThe program includes talks and demonstrations of handicraft techniques, as well as cultural performances, the remarkable Purnima Ghosh dancer made in one of the sessions dressed in a hand -painted Batik Sari. Batik involves drawing designs on fabric with hot liquid wax and a metal object. Then, artists use fine brushes to paint dyes inside wax contours.

“The objective is to attract attention to Bengala’s shared legacy with Bangladesh, be it textiles, techniques, skills and trades, as well as narrative stories, culture and food, despite the changing geographies,” says Darshan Mekani Shah, founder of the Weovers Study Resources Center, which is celebrating the exhibition.

In other places, curators are trying to introduce a more nuanced understanding of the history of textiles in India, including the ways in which it has been influenced by greater social realities of castes and class struggles.

Weovers Studio Resource Center

Weovers Studio Resource CenterTake Pampa: Karnataka textiles presented by the Aberaj Baldota Foundation that ended earlier this month in Hampi, a Unesco World Heritage site. Among the hundreds of textiles at exhibition was the work of embroidery of the Lambanis, a local nomadic tribe; Kaudi mats created by the state’s Siddhi community, which tracks its origins to Africa; as well as sacred textiles made for Buddhist monasteries.

Through these representations, the program tries to tell the stories of the nomadic, tribal and agrarian communities for whom the resistant survival was the leitmotif and the fabric a way of narrating their marginalized experiences.

And it is not just about history, some exhibitions also highlight the future of the industry, since designers find new and innovative ways to imagine traditional textiles in a contemporary language.

ABHERAJ BALDOTA FOUNDATION

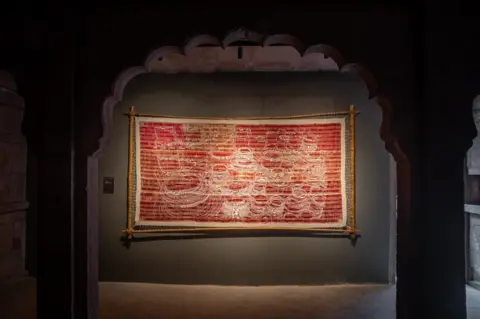

ABHERAJ BALDOTA FOUNDATIONFor example, the recently completed surface: an exhibition of Indian embroidery and surface ornaments such as art, goes beyond clothing and decoration of the home and highlights the ways in which textiles are also being used in paintings, drawings, art facilities and sculptures.

The show, organized by the Suutrakala Foundation and held around a hole in the old city of Jodhpur, presented a set of textile art pieces made by the renowned contemporary painter Manisha Parekh.

These programs also play an important role in updating the history of textiles by rigorously documented.

“Even some of the largest fashion institutes in the country do not have a archive of our textiles,” says Lekha Poddar, co -founder of Devi Art Foundation, which has supported nine exhibitions in textiles in the last decade.

Sutrakala Foundation

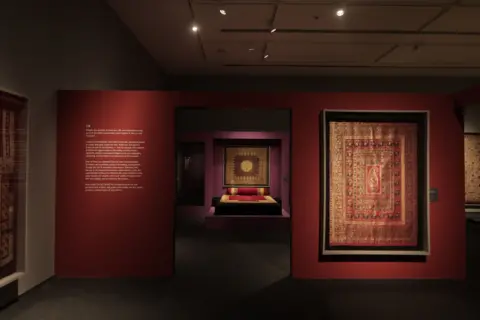

Sutrakala FoundationThe recent project of the foundation of the Devi Art, entitled Pehchaan: Durable themes in Indian textiles, has tried to close that gap.

Presented in collaboration with the National Museum of Delhi, the show presented a survey of visual and material ideas that have resorted to Indian textiles for more than 500 years, with the oldest exhibition that goes from the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries.

“How will young inspiration find their work if they are not aware of their own stories and have no visual references for it?” Mrs. could question.

The success of these programs has made the organizers wait for their future.

The next few years are trying to promote this creative ecology, says Mayank Mansingh Kaul, who has served as a curatorial advisor of 20 exhibitions of this type in the last 10 years.

“Little by little, we will build new audiences, we will collaborate more and push the next generation of manufacturers and practitioners to aspire to quality.”

Follow BBC News India in Instagram, YouTube, Twitter and Facebook.