Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Lizzy Steel/BBC

Lizzy Steel/BBC“I don’t want my last act on this planet to be a polluting act, if I can help it,” explains Rachel Hawthorn.

She is preparing to make her own shroud because she is concerned about the environmental impact of traditional burials and cremations.

“I try very hard in my life to recycle and use less, and to live in an environmentally friendly way, so I want my death to be that too,” he adds.

A gas cremation produces the estimated equivalent carbon dioxide emissions of a return flight from London to Paris and around 80% of those who die in the UK are cremated each year, according to a report from carbon consultancy Planet Mark.

But traditional burials can also pollute. Non-biodegradable coffins are often made with harmful chemicals and bodies are embalmed with formaldehyde – a toxic substance that can leach into the soil.

Lizzy Steel/BBC

Lizzy Steel/BBCin a recent survey According to Co-op Funeralcare, run by YouGov, one person in 10 said they would want a more “green” funeral.

Rachel, from Hebden Bridge, West Yorkshire, made a shroud for a friend from locally sourced wool, willow, bramble and ivy, as part of her work as an artist.

For years she has explored the themes of death, dying, grief and nature through crafts and functional objects.

But the 50-year-old sees the shroud, which can also eliminate the need for a coffin, as more than just a work of art, and has since decided to make her own.

A common reaction from those who have seen the creation is to ask if they can touch it, feel how soft it is.

For Rachel, it’s the perfect way to help people address the taboo topic of death.

She also works as a death doula, which involves supporting people who are dying, as well as their loved ones, to make informed decisions about funeral care.

“I think when we talk about death, everyone I’ve ever met thinks of it as something useful and healthy and something that enriches life,” he says.

“When someone dies, it is often very shocking. We just get into a rut of ‘this is what happens’, so I want to open up those conversations.

“I want more people to know that there are options and that we don’t have to end up in a box.”

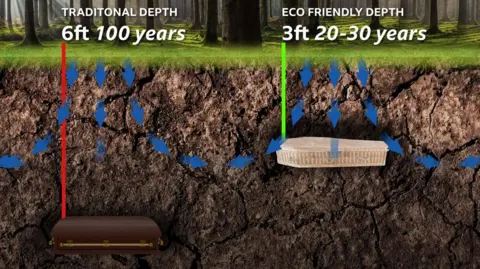

The practice of digging graves to a depth of 6 feet (1.82 m) dates back to at least the 16th century and is believed to have been a precaution against plague.

When Rachel’s time comes, she wants a natural burial, which means using a biodegradable casket or shroud in a shallower grave. The upper layers of soil contain more active microbes, so bodies can decompose in about 20 to 30 years, rather than up to 100 in a traditional grave.

Natural cemeteries are spread across the UK and bear little resemblance to normal cemeteries: trees and wildflowers replace man-made grave marks and no pesticides are used.

Embalming, headstones, decorations and plastic flowers are not permitted.

Louise McManus’s mother was buried last year at Tarn Moor Memorial Woodland, a natural site near Skipton. The funeral included an electric hearse, a locally made wool coffin and flowers from her garden.

“He loved nature and being outdoors. She was concerned about what was happening to the environment and asked that her funeral be as sustainable as possible,” says Louise.

Sarah Jones, the director of the Leeds-based funeral home that organized the farewell, says demand for sustainability is growing.

Their business has expanded to four locations since opening in 2016 and the rise of sustainable funerals has helped fuel that expansion.

He said that of a “handful” of green burials, these types of requests now account for about 20% of his business.

“More and more people are asking about it and want to make decisions that are better for the planet. They often feel that it reflects the life of the person who has died because it was important to them,” he says.

Lizzy Steel/BBC

Lizzy Steel/BBCAs with many green industries, natural burials can cost more. Many estates, including Tarn Moor, offer cheaper pitches to locals. One in Speeton, North Yorkshire, is run by the community and returns profits to the village playground.

At Tarn Moor, a plot plus maintenance for Skipton residents costs £1,177. Foreigners pay £1,818. The nearest municipal cemetery charges £1,200 for a grave, while cremation costs here start at £896.

Often far from urban areas and transport links, traveling to natural grounds for funerals or visiting a grave can involve a larger carbon footprint than more traditional sites, the Planet Mark report notes.

Rachel, the maker of Shrouds, recognizes these challenges, but expects long-term changes. He wants to see more local natural spaces and normalize green funeral care, while respecting the decisions of others.

“In times past, women would come to their marital home with their shrouds as part of their dowry and keep them in the bottom drawer until they were needed,” he says.

“I don’t see why people can’t have their shroud ready and waiting for them.

“I think it could be that normal, but everyone has to make their own decisions about it. “It doesn’t have to be a certain way.”