Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

In Georgia, archaeologists were working in tall summer grass while conducting test excavations at a 3,000-year-old fortress. But when they returned in the fall, they discovered that the flora was hiding something shocking before.

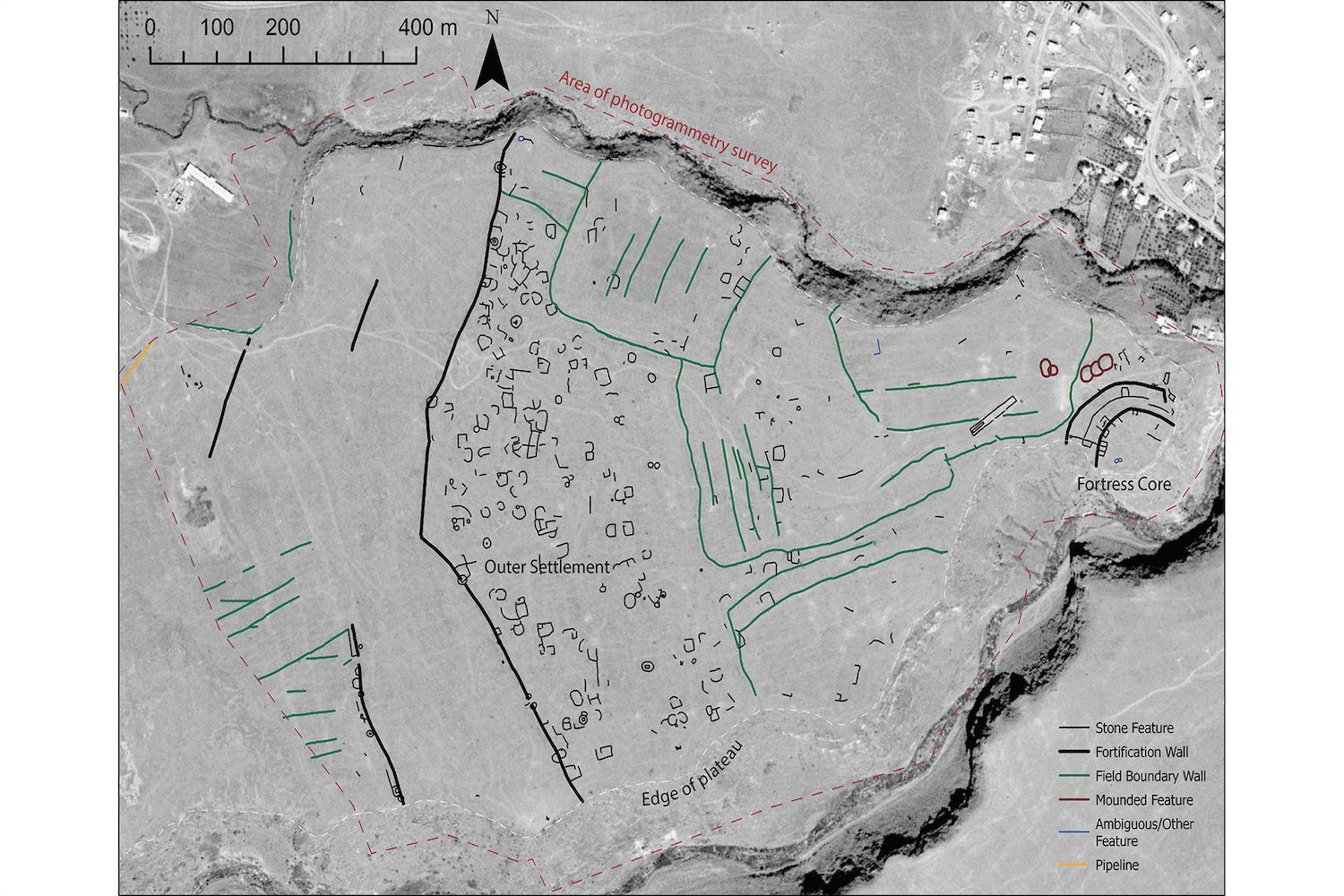

Researchers from the UK, Georgia and the US have used drone technology to map the spread of Dmanisis Gora, a Bronze Age “megagala” in the Caucasus Mountains, and found the complex to be 40 times larger than previously thought. Their research is detailed in a Jan. 8 study published in the journal Antiquitycan provide information on patterns of ancient settlement growth and urbanization worldwide.

“The use of drones allowed us to understand the significance of the site and document it in a way that was not possible on the ground,” said Nathaniel Erb-Satullo of the Cranfield Institute of Justice, who participated in the study. at Cranfield University statement. “Dmanisis Gora is not only an important find for the South Caucasus region, but also has wider significance in terms of diversity in the structure of large-scale settlements and their formation processes.”

The Caucasus is a geographic region that includes parts of Russia, Georgia, Azerbaijan, and Armenia, and is an ancient crossroads of many different cultures, including indigenous peoples. According to the research, large fortress settlements began to emerge in the South Caucasus region in 1500-500 BC.

Erb-Satullo and her co-director, Dimitri Cachvliani of the National Museum of Georgia and research participant, began investigating Dmanisis Gora in 2018. After initial test excavations, the team returned to find that the fall landscape had revealed additional fortification walls and castle walls. stone structures far from the inner fortress they had previously discovered. The complex was much larger than they thought, but they found it impossible to document how much larger it was from the ground.

“That led to the idea of using a drone to assess the site from the air,” Erb-Satullo said. The researchers used a drone to take almost 11,000 photos of the site, which they then combined to create digital elevation models and orthophotos: aerial photographs adjusted to account for elements such as the angle at which the photograph was taken.

“These data sets allowed us to identify fine topographical features and create accurate maps of all the fortification walls, tombs, field systems and other stone structures at the outlying settlement,” added Erb-Satullo. “The results of this survey showed that the site, including a large outlying settlement protected by a 1 km long fortification wall, was more than 40 times larger than originally thought.” One kilometer is approximately 0.62 miles.

Erb-Satullo and colleagues then compared the orthophotos with Cold War-era spy satellite imagery to analyze how the site has evolved over the past five decades, highlighting the encroachment of modern agriculture.

Although modern expansion threatens the site, researchers hypothesize that thousands of years ago, Dmanisis Gora experienced impressive urban growth “thanks to interactions with mobile pastoral groups,” Erb-Satullo explained. “Its large external settlement may have expanded and contracted seasonally,” he said.

The team now hopes to use the newly collected data to further investigate elements such as population density and intensity, livestock movements and agricultural practices.

Finally, the drone map of Dmanisis Gora sheds light on the megagala as well as on broader patterns of Late Bronze and Early Iron Age societies as a whole. This is another example spy satellite images that lend a hand to archaeologists have been declassified decades after the photographs were taken.