Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

fake images

fake imagesWe are in the year 1000 AD, the heart of the Middle Ages.

Europe is constantly changing. The powerful nations we know today (such as Norman-ruled England and the fragmented territories that would become France) do not yet exist. The imposing Gothic cathedrals have not yet been built. Apart from the distant and prosperous city of Constantinople, few large urban centers dominate the landscape.

However, that year, on the other side of the world, a South Indian emperor was preparing to build the most colossal temple in the world.

Completed just 10 years later, it was 66 m (216 ft) high and assembled from 130,000 tons of granite: second in height only to the pyramids of Egypt. At its heart was a 12-foot-tall emblem of the Hindu god Shiva, sheathed in gold inlaid with rubies and pearls.

In its lamp-lit room there were 60 bronze sculptures, adorned with thousands of pearls extracted from the conquered island of Lanka. In his treasures are several tons of gold and silver coins, as well as necklaces, jewelry, trumpets and drums taken from defeated kings throughout the southern Indian peninsula, which made the emperor the richest man of the time. .

He was called Raja-Raja, King of Kings, and belonged to one of the most amazing dynasties of the medieval world: the Cholas.

His family transformed the way the medieval world worked; however, they are largely unknown outside India.

fake images

fake imagesBefore the 11th century, the Cholas had been one of many contending powers that dotted the Kaveri floodplain, the great mass of silt that flows through the present-day state of Tamil Nadu in India. But what distinguished the Chola was their infinite capacity for innovation. By the standards of the medieval world, the Chola queens were also notably prominent and served as the public face of the dynasty.

The Chola widow Sembiyan Mahadevi, Rajaraja’s great-aunt, traveled to Tamil villages and rebuilt small, ancient mud shrines with shining stone and “renamed” the family as the main devotees of Shiva, gaining them a popular following.

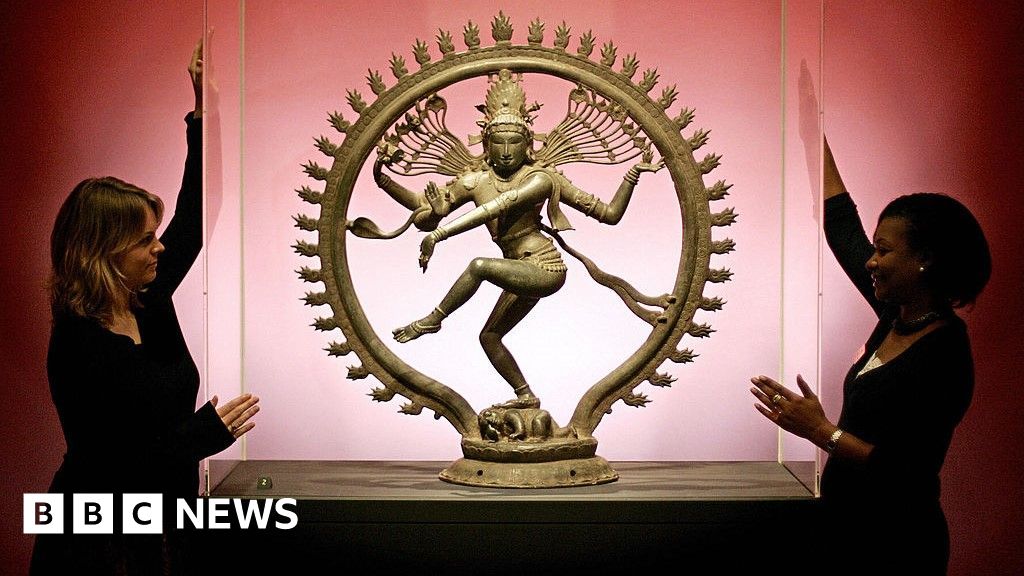

Sembiyan prayed to Nataraja, a hitherto little-known form of the Hindu god Shiva, as King of Dance, and all his temples featured him prominently. The trend became popular. Today Nataraja is one of the most recognizable symbols of Hinduism. But to the medieval Indian mind, Nataraja was actually a symbol of the Cholas.

Emperor Rajaraja Chola shared his great-aunt’s taste for public relations and devotion, with one significant difference.

Rajaraja was also a conqueror. In the 990s, he led his armies on the Western Ghats, the range of hills protecting India’s western coast, and burned his enemies’ ships while they were in port. Then, taking advantage of the internal turmoil on the island of Lanka, he established a Chola outpost there, becoming the first mainland Indian king to establish a lasting presence on the island. Finally, he broke into the rugged Deccan plateau (from Germany to coastal Tamil Italy) and took over part of it.

fake images

fake imagesThe spoils of conquest were lavished on his great imperial temple, known today as Brihadishvara.

In addition to its precious treasures, the great temple received 5,000 tons of rice a year, from conquered territories throughout southern India (today a fleet of twelve Airbus A380s would be needed to transport that amount of rice).

This allowed the Brihadishvara to function as a mega-ministry of public works and welfare, an instrument of the Chola state, intended to channel Rajaraja’s vast fortunes into new irrigation systems, into crop expansion, and into huge new herds of sheep and buffaloes. . Few states in the world could have conceived of economic control on such a scale and depth.

The Cholas were as important to the Indian Ocean as the Mongols were to the interior of Eurasia. Rajaraja Chola’s successor, Rajendra, forged alliances with Tamil trading corporations: a partnership between merchants and government power that foreshadowed the East India Company (a powerful British trading corporation that later ruled much of India) that was to come. 700 years later.

In 1026, Rajendra sent his troops to merchant ships and sacked Kedah, a Malay city that dominated the world trade in precious woods and spices.

While some Indian nationalists have proclaimed this to be a Chola “conquest” or “colonization” in Southeast Asia, archeology suggests a stranger picture: The Cholas did not appear to have a navy of their own, but beneath them, a wave of Tamils Diaspora traders spread across the Bay of Bengal.

By the end of the 11th century, these merchants operated independent ports in northern Sumatra. A century later, they lived in what is now Myanmar and Thailand, and worked as tax collectors in Java.

AFP

AFPIn the 13th century, in Mongol-ruled China under the descendants of Kublai Khan, Tamil merchants ran successful businesses in the port of Quanzhou and even erected a temple to Shiva on the coast of the East China Sea. It was no coincidence that, under the British Raj in the 19th century, Tamils constituted the bulk of Indian administrators and workers in Southeast Asia.

Global conquests and connections made Chola-ruled South India a cultural and economic giant, the nexus of planetary trade networks.

Chola aristocrats invested the spoils of war in a wave of new temples, reaping excellent assets from a truly global economy linking the farthest shores of Europe and Asia. The copper and tin for their bronzes came from Egypt, perhaps even Spain. Camphor and sandalwood for the gods came from Sumatra and Borneo.

Tamil temples grew into vast complexes and public spaces, surrounded by markets and dotted with rice plantations. In the Chola capital region of Kaveri, corresponding to the present-day city of Kumbakonam, a constellation of a dozen temple cities supported populations of tens of thousands of people, possibly surpassing most cities in Europe at the time. .

These Chola cities were strikingly multicultural and multi-religious: Chinese Buddhists rubbed shoulders with Tunisian Jews, Bengali tantric masters traded with Lankan Muslims. Today, the state of Tamil Nadu is one of the most urbanized states in India. Many of the state’s cities grew up around shrines and markets of the Chola period.

fake images

fake imagesThese developments in urban planning and architecture had parallels in art and literature.

Medieval Tamil metalwork, produced for the temples of the Chola period, is perhaps the best ever made by human hand; artists rival Michelangelo or Donatello for their appreciation of the human figure. To praise the Chola kings and worship the gods, Tamil poets developed notions of sanctity, history and even magical realism. The Chola period was what you would get if the Renaissance had occurred in South India 300 years before your time.

It is no coincidence that Chola bronzes, especially the Nataraja bronzes, can be found in most major Western museum collections. Scattered around the world, they are the remains of a period of brilliant political innovations, of maritime expeditions that connected the globe; of titanic sanctuaries and fabulous riches; of merchants, rulers and artists who shaped the planet we live on today.

Anirudh Kanisetti is an Indian writer and author, most recently of Lords of Land and Sea: A History of the Chola Empire