Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Getty images

Getty imagesA shorter winter has literally left Nitin Goel in the cold.

For 50 years, his family’s clothing business in the textile city of Ludhiana in the northwest of India has made jackets, sweaters and sweatshirts. But with the early summer start this year, the company is watching a washing season and has to change their march.

“We have had to start t -shirts instead of sweaters as winter is shortening with each year passing. Our sales have been reduced by half in the last five years and have dropped 10% more during this season,” Goel told the BBC. “The only recent exception to this was Covid, when temperatures fell significantly.”

Throughout India, as the cold climate exceeds a hurried retirement, anxieties are accumulating in farms and factories, with cultivation patterns and business plans that become.

Nitin Goel

Nitin GoelThe data of the Indian Meteorology Department show that last month was the most popular in India in February in 125 years. The average weekly minimum temperature was also above normal in 1-3 ° C in many parts of the country.

It is likely that maximum temperatures and heat waves above normal persist in most parts of the country between March and May, the weather agency warned.

For small businesses such as Goel, such erratic climate has meant much more than just slowing sales. All your business model, practiced and perfected for decades, has had to change.

Goel’s company supplies clothing to multiple brands of sale throughout India. And they are no longer paying to delivery, he says, instead adopting a “sale or return” model where the shipments not sold are returned to the company, completely transferring the risk to the manufacturer.

He has also had to offer greater discounts and incentives to his clients this year.

“The big retailers have not collected products despite confirmed orders,” says Goel, and adds that some small businesses in their city have had to shut up as a result.

Getty images

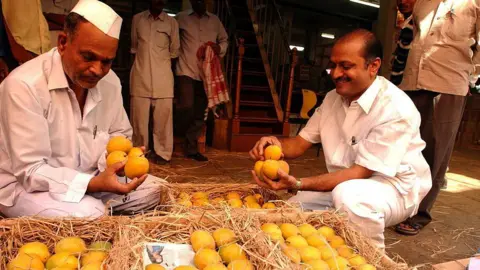

Getty imagesAlmost 1,200 miles away in the city of Devgad on the western coast of India, heat has wreaked havoc on the very beloved mango orchards of Alfonso de la India.

“This year’s production would be only about 30% of normal performance,” said Vidyadhar Joshi, a farmer owner of 1,500 trees.

The sweet, fleshy and richly aromatic Alfonso is a precious export of the region, but the yields in the districts of Raigad, Sindhudurg and Ratnagiri, where the variety is predominantly cultivated, are lower, according to Joshi.

“We could make losses this year,” says Joshi, because he has had to spend more than usual in irrigation and fertilizers in an attempt to save the harvest.

According to him, many other farmers in the area even sent workers, who come from Nepal to work in the orchards, at home because there was not enough to do so.

The scorching heat also threatens the basic winter foods such as wheat, chickpeas and rapes.

Although the country’s minister of agriculture has dismissed concerns about low yields and predicted that India will have a twin wheat harvest this year, independent experts have less hope.

Heat waves in 2022 lowered the yields by 15-25% and “similar trends could follow this year,” says Abhishek Jain, of the Energy, Environment and Water Council (CEEW), group of experts.

India, the second largest wheat producer in the world, will have to depend on expensive imports in case of such interruptions. And its prolonged exports prohibition, announced in 2022, can continue even more for longer.

Getty images

Getty imagesEconomists are also concerned about the impact of the increase in temperatures on water availability for agriculture.

The levels of deposits in northern India have already fallen to 28% of the capacity, below 37% last year, according to CEEW. This could affect the yields of fruits and vegetables and the dairy sector, which has already experienced a decrease in milk production of up to 15% in some parts of the country.

“These things have the potential to boost inflation and reverse the objective of 4% of which the Central Bank has been talking,” says Madan Sabnavis, chief economist of the Banco de Baroda.

Food prices in India have recently begun to be softened after staying high for several months, which leads to rates cuts after prolonged pause.

GDP in the third largest economy in Asia has also been supported by accelerating rural consumption recently after reaching a minimum of seven quarters last year. Any setback to this recovery led by the farm could affect general growth, at a time when urban households have been reducing and private investment has not recovered.

The Think Tanks such as CEEW say that you should think of a variety of urgent measures to mitigate the impact of recurrent heat waves, including a better time prognosis infrastructure, agricultural insurance and evolving cultivation calendar with climatic models to reduce risks and improve yields.

As a mainly agrarian country, India is particularly vulnerable to climate change.

CEEW estimates that three out of four Indian districts are “extreme events access points” and 40% exhibits what is called “an exchange trend”, which means that the areas traditionally prone to floods are witnesses of droughts and more frequent and intense vice versas.

The country is expected to lose around 5.8% of daily work hours due to heat stress by 2030, according to an estimate. Climate transparency, the Defense Group, had set the potential loss of income of India in the sectors of services, manufacturing, agriculture and construction due to the reduction of work capacity due to the extreme heat of $ 159 billion in 2021 or 5.4% of its GDP.

Without urgent actions, India runs the risk of a future in which heat waves threaten both life and economic stability.

Follow BBC News India in Instagram, YouTube, unknown and Facebook.